Weekly Inflation Outlook – it is over

2022.06.27 16:11

Weekly Inflation Outlook – it is over.

As theater goes, the semiannual Monetary Policy Report to Congress (MPC) testimony is pretty thin gruel. But beggars can’t be choosers and, after all, we signed up for this when we decided to be investors. Anyone want a do-over?

The MPC was originally called the Humphrey-Hawkins testimony, after the legislators whose names were on the original 1978 legislation ordering the Chairman of the Federal Reserve to transmit a report to Congress twice a year and to testify before the relevant House and Senate committees.

The report itself is dreadful reading, but financial historians can sometimes find interesting things in the testimony. For example, here is a fun nugget from the February 1980 hearing in front of the House of Representatives Committee on Banking, Finance, and Urban Affairs:

Chairman Reuss:

“Chairman Volcker, welcome to your first appearance before this committee in its semiannual monetary policy review. Last year, following our first hearings, under the procedures established in Humphrey-Hawkins, we issued a report on Mar. 12, 1979, agreed to by all except one of our members. The key recommendation of that report was ‘anti-inflationary policies must not cause a recession.’ So far, the Federal Reserve’s policies have not caused a recession and for that, you deserve our appreciation…

For 1980, dangers remain. First and foremost, inflation is simply out of control. There are some signs of a weakening economy. Caution is needed…The Federal Reserve cannot cure inflation with monetary shock treatment and it shouldn’t try. Inflation can be stopped only by a program of structural reform fortified by mandatory energy conservation and an effective incomes policy…

Times change, but it remains the case that politicians always want to lose weight without dieting. Over the years, as the Fed has become more and more transparent—to the degree that the Chairman now has regular press conferences following FOMC meetings—the Fed also has sought benefits without consequences. The current tightening regime is the latest iteration of the attempt to find the perfect diet: raise interest rates, while maintaining an environment of copious liquidity, and just maybe “a recession isn’t inevitable.”

Do they really believe that? Do they think that they can raise interest rates several hundred basis points, while energy prices double, and not produce a recession?

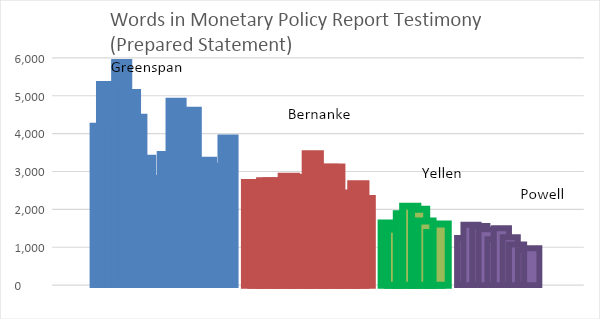

I don’t think they believe that, and to his credit Chairman Powell is not exactly screaming his confidence in such an outcome. In fact, he’s barely talking at all—at least, to the people he’s required to talk to. Powell basically tied his own record this month for the fewest words in his prepared statement to Congress. I am not entirely sure about the significance of the following chart, but I think it may be a sign of the increasing hubris of the central bank. Greenspan had many faults, but at least in his testimony, he would lay out his full thinking as thoroughly as he could. Does the increasing brevity of the statements of the Fed Chair indicate that they don’t think as much, or that they don’t think they should tell us what they’re thinking?

Words In Monetary Policy Statement

Words In Monetary Policy Statement

For example, it would be really great to get further illumination on this statement made by Chairman Powell, which has been echoed scores of times by Fed speakers:

“We have both the tools we need and the resolve it will take to restore price stability on behalf of American families and businesses.”

Actually, back in 2020, the statement was subtly different. In 2020 and early 2021, policymakers at the Fed and Treasury were chanting that they have the tools to prevent inflation, knew how to use them, and had the will to do so.

Business Headline

Business Headline

Taking a Step Back…

It is true that the Fed has the tools they need to restrain inflation. Moreover, I believe that they could in principle restrain inflation without causing a recession, except for the fact that energy prices are also spiking. But I do not think that the Federal Reserve actually knows how to use the tools. They just seem to believe so many things that aren’t so and about which we have strong evidence that they don’t work. Consider this remark from Chairman Powell in testimony this week:

“The point is that if the public retains confidence that inflation will come down, then it will come down,” Jerome Powell, June 23, 2022.

For starters, it’s worth pointing out that if it’s important that the public have confidence in the Fed, then perhaps fewer words might, in fact, be better. Since it seems most of their words seem to be wrong these days: Inflation isn’t going to rise. It’s rising, but that’s just transitory. Inflation will recede to 2% by the end of 2022. Well, perhaps 4%. There’s no sign of recession…

But the bigger point is that there is just no evidence that prices respond to what consumers want them to do. If they did, then we should just all desire lower prices and we could watch them decline. Come to think of it, don’t we all in fact desire lower prices? It’s pretty nonsensical on its face to think that if a widget costs 20% more to make this year, but consumers don’t “accept” the increase in price, the price will not rise. It’s not even good economics. ECON 101 tells us that if the supply curve shifts to the left, we get higher prices unless the demand curve is completely elastic.

Ivory tower economists think expectations matter because it really makes their models work better if they introduce such anchoring. Many inflation models can be fit to the post-1992 period or to the pre-1992 period, but there is a parameter state-shift around 1992 which means it is very difficult to fit both periods. That is unless we “assume a can opener” and posit that something changed in 1992. That something, according to the bow-tied set, is that inflation expectations suddenly became anchored in 1992 thanks to the tremendous success that the Fed had had in bringing inflation lower. Although it must have been difficult to write all those papers while simultaneously patting themselves on the back, this is essentially where the “expectations-augmented Phillips Curve” notion came from.

But this notion has come under serious pressure over the last couple of years. And a seriously introspective and honest Federal Reserve could not realistically ignore the total takedown of this notion that Dr. Jeremy Rudd, a Senior Adviser in the Fed’s Research and Statistics Division, published last year as part of the Finance and Economics Discussion Series at the Fed. In short, he argues persuasively that the basis for the belief in the role-anchored inflation expectations rests on very shaky theoretical and empirical grounds. While other economists may disagree, it is at least disingenuous for the Fed Chairman to continue to insist on the primacy of this idea when it is (a) very critical to the medium-term outlook and (b) in serious question.

But perhaps that’s the reason Powell’s testimony has been so brief lately. As the saying goes, “better to remain silent and be thought a fool, than to speak and remove all doubt.”