Weekly Inflation Outlook: Inflation Is Peaking, but Spending Will Keep It Around

2022.11.14 15:43

[ad_1]

Despite what you may have read last week, the downward surprise in is not a sign that inflation is about to collapse, that the Fed has won, and that rates will soon be in full-throated retreat since recession is the likely next act.

To be sure, the cyclical highs for are in, even though median inflation is going to be accelerating for another couple of months at least and will end 2022 above 7%. After that, median inflation will probably decelerate, but probably not head back to 2.5%. The world has changed in many ways which will be persistent. One of these is that re-onshoring and near-shoring are reversing the two-decade-old trend towards off-shoring production to the lowest-cost country. Core goods inflation, which is decelerating, is not likely to return to its old -1%-0% sort of range but more like 1%-2%. The demographic challenge, which reduces the supply of labor for service industries, will place upward pressure there.

And to that list, we can now also add that the era of large government spending programs—which I thought might be coming to at least a temporary hold when pollsters told us the Republicans were going to win a mighty electoral victory—is going to continue for at least a couple of years. At this writing, we know that Democrats will continue to hold the majority in the Senate and may even expand their influence by 1 seat, and in the House of Representatives, the best the Republicans can hope for is a tiny majority. That would flip the gavel and change the chairmanship of all House committees, but it wouldn’t stop large spending bills from passing with just a mild application of pork barrel spending to the districts the Administration needs to sway. In fact, this argues for fewer but larger packages—so you only need to ‘buy’ votes once. As the economy looks to be headed into a recession in 2023…as I’ve said for a long time…we can expect generous stimulus packages will be headed our way.

It is worth remarking that if increasing deficit spending is not accommodated by the Fed, it need not be as overtly inflationary. But I don’t know that the Fed will be able to stand by. In addition to any “one time” stimulus spending, the cost of Social Security is about to rise by nearly 9% next year along with Medicare cost increases and, most ominously, a meaningful increase in the interest paid on the debt. Absorbing more trillions in a 4% inflation environment would call for higher bond yields—which would be further budget-busting. If the bond bear market continues, there will be calls for the Fed to step in and moderate the decline by buying bonds. So stay tuned.

One other note this week. On Nov. 3, Canada announced that it was ceasing issuance of Real Return Bonds (RRBs). Many readers will not be familiar with RRBs, but that market pre-dates TIPS by six years and the structure of RRBs was the model on which TIPS—and all subsequent inflation-linked sovereign bond markets—was based. The RRB market has been illiquid for a while, because Canada doesn’t issue enough for the pension funds that have inflation-linked liabilities. Ergo, when a new RRB is issued, it vanishes into portfolios never to be seen again. The Canadian announcement blamed the illiquidity on a “lack of demand” in deciding to cease issuance, and that is patently false. It’s like saying you could tell there was no demand for COVID vaccines in mid-2020, because there weren’t any lines for them. The lines definitely formed, once there were vaccines available! This announcement by Canada’s Department of Finance is like taking COVID vaccines off the market at the height of the pandemic. The inflation disease is infecting everyone, and Canada has said “find medicine somewhere else.” It is a terrible decision, and we can only cross our fingers and hope that other governments don’t use the “lack of demand” argument to opportunistically eliminate auctions of bonds that are currently somewhat expensive (and politically awkward) for the government issuers.

Taking a Step Back…

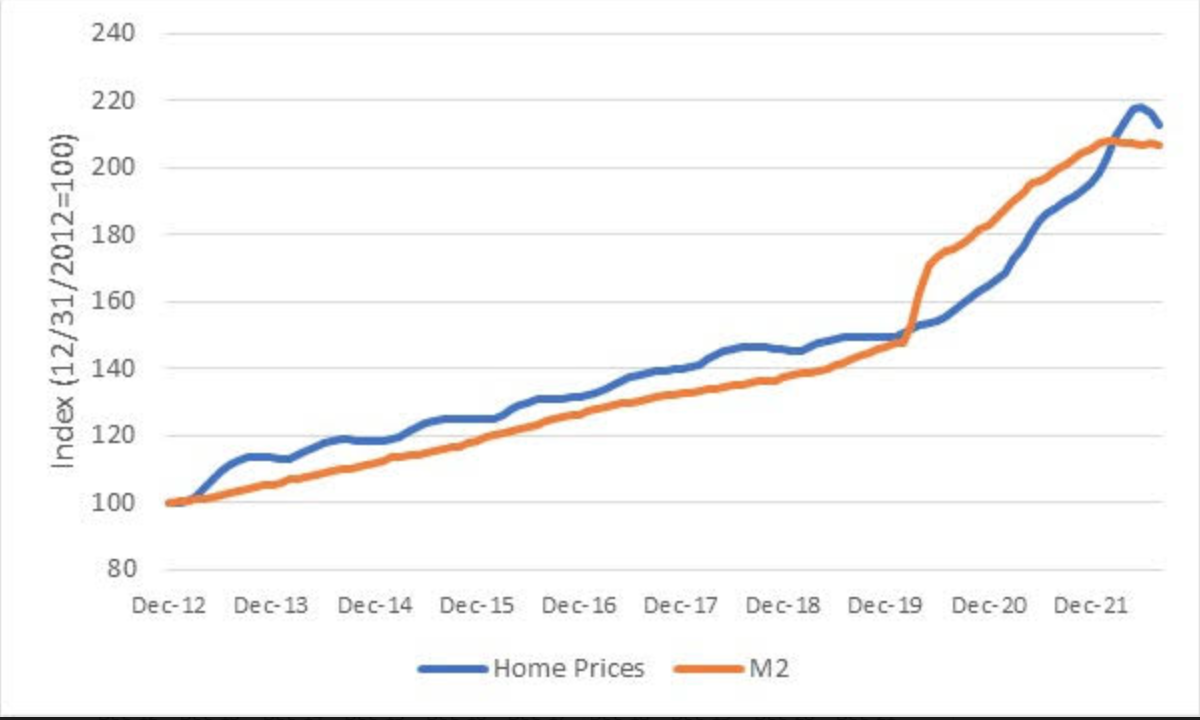

I have previously shown the chart of home price growth in this cycle versus money supply growth, making the point that there is nothing surprising with the price of a real asset going up 40% when the quantity of money goes up 40%. Here is that chart again; I am showing it because I want to address one objection that has been directed at it. The chart (source: S&P, Federal Reserve) is indexed to December 2012. The increase in money implies that not just home prices, but the average price level in general, will eventually converge at a higher level even if the rate of increase slows from 7% to, say, 4%. This increase in home prices, then, shouldn’t be surprising.

House Price Increases Vs. M2

House Price Increases Vs. M2

But some people have claimed that I cherry-picked this period and excluded the prior bubble period, when home prices did not track the money supply. Here is the analogous chart from that period.

House Price Increases Vs. M2

House Price Increases Vs. M2

Not to put too fine a point on it, but it is exactly the point that in the 2004-2006 period, home prices exceeded the growth rate of money by a substantial amount. That is the reason that the earlier period was clearly a bubble at the time, while this period is clearly not a bubble. That isn’t to say that home prices will continue to keep up with inflation. If home prices have already mostly adjusted to the increase in the money supply then we would expect further gains from here to be more limited and to lag behind inflation. In other words, real home price increases will likely be negative. Enduring’s estimate is that residential real estate is priced to return -2.14% per year for a decade after inflation. But in a world of 4% inflation, which is the world we are now living in, that means that nominal home prices should not fall very far, for very long.

Disclosure: My company and/or funds and accounts we manage have positions in inflation-indexed bonds and various commodity and financial futures products and ETFs, that may be mentioned from time to time in this column.

[ad_2]

Source link