Weekly Inflation Outlook: Enough Inflation Poison Eventually Makes Stocks Sick

2022.10.03 14:18

[ad_1]

Stepping into the spooky month (from a historical market perspective, of course) of October, we need to take administrative notice of the fact that the has fallen more than 8% in three of the last six calendar months. Without July’s rollicking 9% rally, we’d be 31% down from the high at 3286 and could start thinking about where the bear market might end.

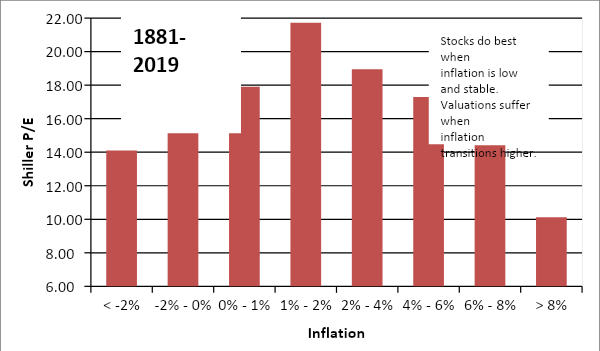

It seems like a good time to remember that inflation is absolutely poison to equities. Wall Street loves to tell you that stocks are an inflation hedge, but that’s a lie and an easily-provable lie at that. Moreover, it isn’t news that stocks aren’t an inflation hedge: in an article in the Journal of Finance in 1976, Zvi Bodie cogently and snidely made the case that common stocks can only be used as a hedge because they can be shorted. Modigliani and Cohn, in “Inflation, Rational Valuation and the Market” (1979 Financial Analysts Journal), argued that the market was wrong to discount equity earnings by the nominal interest rate (which causes multiples to contract in inflationary periods)…but it does. And, empirically, the data is unequivocal: multiples are highest when inflation is low and stable, and lowest when inflation is high and unstable.

P/E Multiples Vs. Inflation

Source: Enduring Investments using Robert J Shiller data

The question is, now that we have had above 8%…are we bound to see stocks trade to a Shiller P/E of 10 (most recently, it was at 26.2)? That would be a tremendous decline from here.

I am sympathetic to the view—though I think it is overdone—that multiples today should be somewhat higher than multiples were 40 years ago. I don’t think it’s for a good reason…but if equity is a call option on the value of the firm (1974, Robert C Merton, so long as we’re citing legendary finance professors), then the proliferation of safety nets for big business which keep them from failing should arguably move that option further into the money, all else equal. That doesn’t mean that a market with a 43x Shiller P/E isn’t expensive, but perhaps it wasn’t overvalued by as much as we thought it was.

Let’s pretend that 43x was fair, for a period when inflation was low and stable (even though by the end of last year many folks recognized inflation was no longer low and stable). In the chart above, multiples contract as we move from 21.7 in the optimal regime, to 10.1 in the ‘inflation ugly’ regime. That’s a 53% decline in the multiple. So if 43x was fair in the former case, then we should not be surprised with 20x now. That would be another 24% decline in stocks from here, assuming perhaps heroically that earnings don’t decline from this level.

If we want to be optimistic and say that inflation is shortly going to be in the 6%-8% bucket, and use the same trick we just did (assume that 43x was fair in the best of times), then 28x is a decent Shiller P/E and the current market level is in the ballpark. In my view, that’s about the most optimistic case valuation-wise and it takes the generous interpretation of a lot of variables.

My guess is that we have some more wood to chop on the downside. I hate to put numbers on these things but if forced to I would nominate 3232 on the S&P 500 as an initial target.

Taking a Step Back…

For a long time, I have expected the Fed to pull off the ball and stop hiking rates so persistently. In full disclosure, I’m on tape as having said the Fed would tighten once or twice and then stop. In my defense, my belief about the Fed’s reaction function was based on my expectation for what the market would do when the Fed started to tighten. It wasn’t that I thought the Fed couldn’t stomach 1% interest rates; it was that I thought the Fed couldn’t stomach a sloppy equity and bond market decline (especially when its models tell it that inflation will mean-revert on its own to 2.5%). And, until now, the decline in stock and bond markets has been very ordinary although signs of illiquidity had been growing in the bond market and I mentioned a couple of weeks ago the disturbing, steady decline in open interest.

Well, now we are starting to get sloppy. The equity decline last week happened on rising volumes. Ten-year yields are up 110bps over the last month. And a few folks may have noticed the U.K. gilt market coming so unglued (+120bps in 1 week and +250bps since mid-August) that the Bank of England was forced to step in to buy and support the market lest pension funds—which had levered low yields to get higher returns—start to collapse.

I don’t know if the Fed will wait until things actually break down before slowing down their , but I wouldn’t be surprised to see some soothing talk come out of them until markets begin to cool down some. But the bottom line remains the same even if the line isn’t drawn where I thought it would be: the ultimate face-off was always doomed to be at the question of whether the Fed can truly stomach the effects of a shrinking balance sheet and shrinking market liquidity in order to bring inflation to heel. I think that at 3% or 4% or even 5% will leave them indifferent. Market volatility that threatens the free functioning of markets, though, is something that threatens one of the Fed’s primary responsibilities and is actually something they have effective tools to deal with. (The problem was always that they fell in love with those tools, and figured that if they were able to let the market down gently why should they let the market down at all?)

We are not about to plunge back to 2% inflation, but we may be getting near the end of vigorous Fed action. To be sure…I have thought that before.

Disclosure: My company and/or funds and accounts we manage have positions in inflation-indexed bonds and various commodity and financial futures products and ETFs, that may be mentioned from time to time in this column.

[ad_2]

Source link