Tidal Wave of Overcapacity Signals Downside for Shipping Industry

2023.03.29 04:29

Last week I wrote an highlighting the sinking global trade volumes and earnings recession that most likely will follow.

And while many corporations and sectors will feel an earnings recession, one area looks very fragile.

I’m talking about global dry shipping – specifically maritime dry bulk.

After two years of elevated freight rates from huge demand and congested ports, prices boomed. Sending maritime shipping stocks through the roof.

But like all capital-cycle-driven booms, they’re the seeds for an inevitable bust. This is exactly what’s happening in the global maritime shipping sector.

And I believe – according to the capital cycle – that things will get worse from here. . .

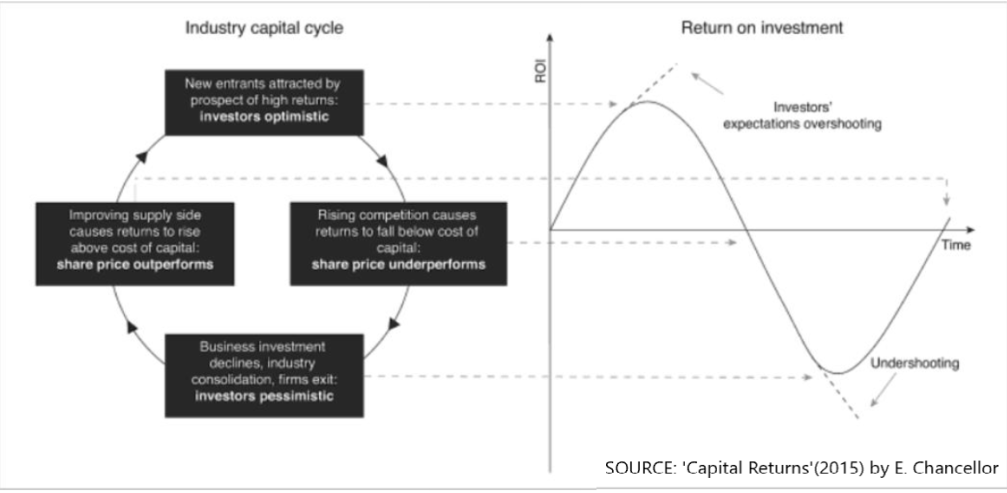

What Exactly Is the Capital Cycle And Why It Really Matters

So, what is a capital cycle, and why does it matter?

To put it simply, it’s about observing how changes in the amount of capital flowing in and out of an industry are likely to impact future returns.

And it also means emphasizing the supply side (often overlooked) more strongly than the demand side (which most analysts prefer).

Now, there’s this little-known book. One that I believe is an absolute must for speculators.

It’s called ‘Capital Returns,’ and it was written by the financial historian – Edward Chancellor. And he goes into the capital cycle extremely closely.

But here’s the gist for those who don’t have time to read it.

Throughout history, returns on investment (ROIs) follow a typical cycle driven by the supply side.

Or said otherwise, the more an industry expands – such as buying assets, taking on debt, increasing capacity, and new entrants – the lower future profits and asset returns will be.

And the more an industry contracts – such as selling assets, deleveraging, shutting down capacity, and bankruptcies – the greater future profits and returns will be.

Hence, this supply-driven boom-and-bust cycle is what Chancellor calls the capital cycle. . .

Chancellor also notes that there’s a strong inverse relationship between capital expenditures (aka CapEx – money invested by a company to grow) and future investment returns.

The famed economist – Eugene F Fama, known for his work on efficient market hypothesis and asset pricing – discovered this. And found there was a long-term negative correlation between contracting and expanding industries.

Or said another way, the sectors contracting for years would outperform the sectors expanding (something that may seem backward).

Fama called this the asset growth anomaly. So, why does this happen?

Because when investment returns are high, it attracts capital (investors and entrepreneurs wanting to get in on it). But new entrants and new capital lead to overinvestment and excess capacity. Eventually creating a glut, declining profits, outflows of capital, and negative returns.

But – like most things – it’s a cycle. Because money is attracted to high-return businesses (boom) and flees when returns fall below the cost of capital (bust).

And eventually – as companies shut down capacity, consolidate, and divest assets (trim the fat), the glut clears. And both profit margins and returns can start to increase. Triggering a renewed wave of investors and capital inflows, and entrepreneurs.

Therefore, bull markets create bear markets. And bear markets create bull markets.

And this dynamic is a big reason why I’m pessimistic about maritime shipping stocks and dry bulk.

Why?

Because shipping companies saw huge returns between 2020-2022 as freight rates soared, thus they expanded capacity at a rapid rate.

But now, as freight rates collapse and a glut of new ships are being built, this signals further downside.

At least, that’s what the capital cycle is telling us.

From Boom to Bust: Global Shipping Is Now Facing a Serious Glut of Capacity Coming Online

Keep in mind that the global shipping industry is pretty complex – dominated by cartels, contract rates, and trade flows.

There are also various types of maritime shipping – such as container-dry bulk, crude-and-natural-gas tankers, etc.

But I’m just going to focus on the capital cycle angle here in the maritime shipping industry as a whole.

Here’s a little context: after the 2020 to early-2022 boom in global trade – as economies reopened from COVID and excess stimulus fueled demand – many shipping companies saw a huge surge in profits and equity prices.

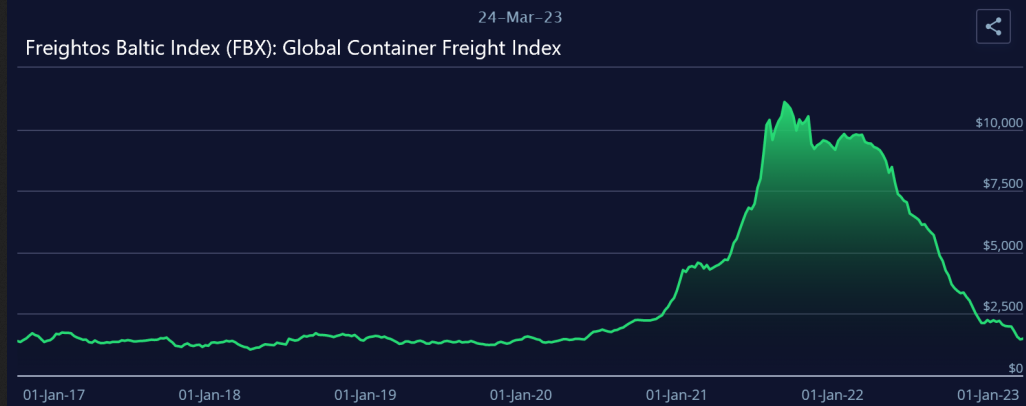

Container shipping freight rates hit a 12-year high amid soaring global demand and supply chain delays.

But – over the last year – demand and growth have cooled considerably. Meanwhile, supply chains began flowing again.

Thus maritime shipping freight rates have completely collapsed.

For perspective – the Freightos Baltic Index (FBX – aka the global container freight index) is down nearly 90% over the last year.

Index – Global Container Freight Index

Index – Global Container Freight Index

The eroding global economy – on the back of tighter credit, smaller government deficits, and diminishing pandemic-era savings – have contributed most to this decline in demand.

Thus lower freight rates were inevitable. But here’s the real problem. . .

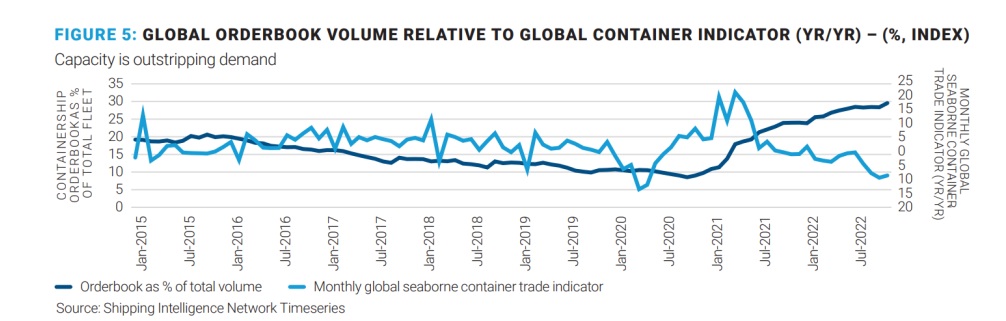

After soaring freight rates and higher global demand from COIVD-stimulus, the maritime shipping sector boomed.

So what did they do?

They began expanding capacity at an alarming rate – expecting the good times to continue.

Thus we’ve seen a wave of new ship orders over the last two years – with a huge amount of this capacity coming online in the next one-three years.

For instance – according to AlixPartners – the global order book volume of new ships (dark blue line) has steadily risen since the second half of 2020.

And even worse, it’s happening at a time when global maritime shipping is declining (light blue line).

So – there’s a wave of excess capacity coming online at a time when demand is already sinking.

This will kill profit margins in shipping companies as the glut of costly-to-build ships competes over the anemic freight rates.

And to put this into perspective – according to AXS Marine – there are currently about 6,500 container ships in service around the world.

These hold a total capacity of roughly 26.3 million 20-foot equivalent unit containers (aka TEUs – a measure of volume units for the 20-foot long container standard).

But in the next two years alone, vessels on order will add 7.48 million TEUs — which is an increase of nearly 30% of total capacity.

This is the largest order book of new containerships in history.

Thus as these global shipping and carrier firms saw surging cash flows over the last two years – they began ordering additional vessels.

Alan Murphy – founder and CEO of Sea-Intelligence – recently said,

“The only thing that scares me more than shipping liens without money is shipping lines with money. . . They spend money on vessels they don’t need. Maybe they should invest in reliability and customer service. That would be my advice.”

Now, these maritime shipping companies are either grossly confident in their future returns (which is historically a very turbulent and unprofitable industry).

Or they’re falling for the capital cycle dilemma (aka expanding at the end of the cycle; producing gluts).

I believe it’s the latter. . .

So – in summary – global maritime shipping saw a good boom for two years. But now it’s entering the bust phase.

After making record profits, these firms are now bringing on a significant amount of capacity at a time when freight rates are plunging back to pre-2019 levels.

This will squeeze margins, force divestment, and most likely lead to further consolidation in the sector (which is already deeply concentrated – with the top 10 companies controlling 85% of the sea).

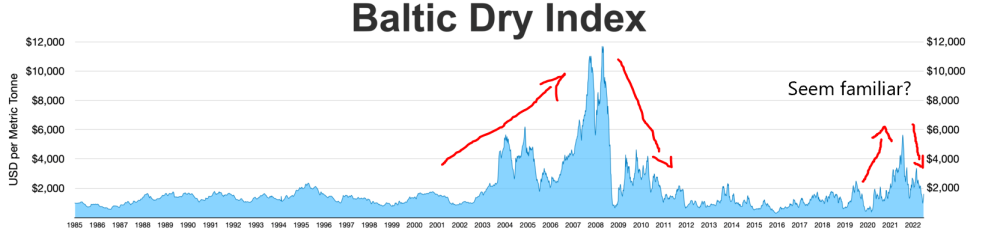

But, it’s not like we haven’t seen this before. . .

Remember, back in the early-2000s, after China was allowed into the World Trade Organization (WTO), the maritime shipping sector (specifically dry-bulk) boomed on the back of rising commodity prices and Chinese growth.

And because of this, the (aka BDI – a measure of the cost of shipping dry bulk goods around the world) soared, hitting a record high in 2008.

Thus as freight rates rose, so did maritime shipping company profits and investment returns. And as capital and new entrants came in, these firms began investing heavily in expanding capacity.

In fact, they were placing ship orders all the way up until 2009. But then the 2008 great financial crisis hit. And global growth plunged, and it remained anemic for the next decade.

Because of this, the BDI collapsed by over 90%, and shipping companies saw their huge profits and returns evaporate as they dealt with overcapacity in a weaker market.

Thus the boom turned into a bust.

Now, unless the global economy today rebounds (unlikely) or there’s magical destruction of ship capacity (not happening), it’s hard to see much upside in the maritime shipping sector.

In fact, it’ll most likely get worse from here – according to the capital cycle.

And this creates contrarian opportunities. Such as finding long-term value plays or attractive asymmetry betting against marginal shippers as their balance sheets erode.

So – as always – keep in mind the capital cycle. And position accordingly.