Stocks Vs. Bonds: Where Should You Allocate for the Next 10 Years?

2023.08.02 13:04

Our recent warns that a tremendous thirty-year tailwind for corporate earnings is dying down. Consistent corporate interest and tax rate declines significantly boosted stock prices and valuations.

However, with effective corporate interest rates near record lows and tax rates at their lowest levels ever, further reductions are improbable. Barring negative interest rates or reductions in corporate tax rates, earnings growth rates in aggregate may shrink 30-50% over the coming decade.

The article’s advice is not necessarily for short-term portfolio management purposes but something all investors should appreciate.

Regarding long-term strategic thinking, it’s worth considering another critical factor for equity investors. There is an alternative. Investors can now lock in a long-term risk-free return of 4% or slightly more.

The question of how much to allocate to stocks versus bonds or other assets should be based on shorter-term fundamental and technical analysis. However, for those inclined to set their investment strategies on long-term factors, the next ten years may differ from what we are accustomed to.

For those in the set-it-and-forget camp, we explain why the combination of bonds with higher yields and our longer-term earnings growth warnings may present an excellent time to reconfigure your stock/bond allocations.

Valuations Matter

Valuations are the prices we pay for investments. It is perhaps the most critical judgment of future returns.

As Warren Buffet once said:

Price is what you pay. Value is what you get.

One’s economic and fundamental outlook may be horrendous. However, an investment can still make much sense at a cheap enough valuation. Conversely, a stock with an extremely high valuation may be predicated on an impossible earnings trajectory. Even in the best of environments, such investments tend to do poorly.

Current Valuations and Future Returns

What does our crystal ball predict based on current valuations?

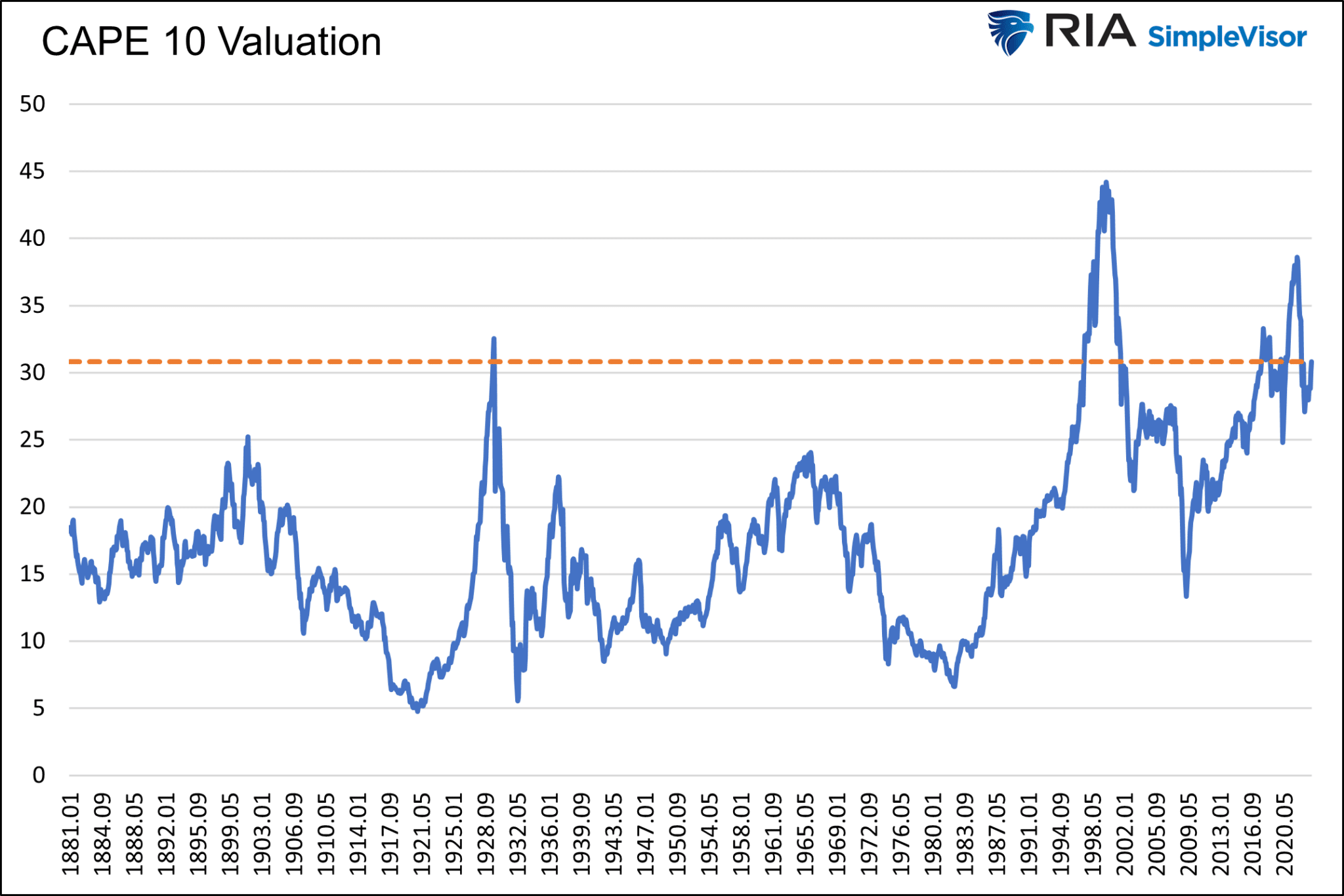

Currently, CAPE 10, a longer-term measure of price to earnings, of the is 30.82. Going back to 1871, today’s valuation has only been exceeded by a brief period leading to the Great Depression, another before the dot com bubble crash, and varying occasions between 2017 and today.

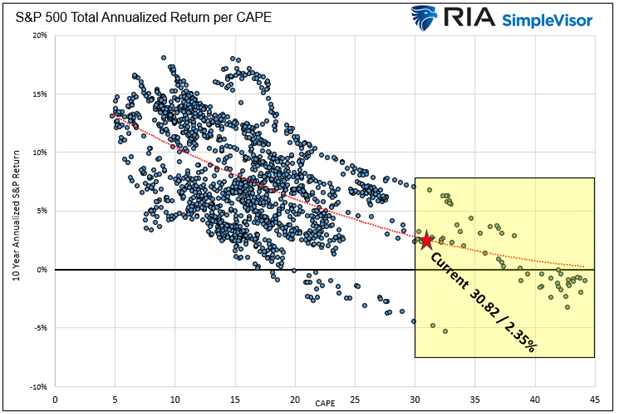

The following scatter plot compares the monthly CAPE valuations with the actual forward ten-year total returns (including dividends).

The red star marks the intersection of the trend line and the current CAPE. Based on a CAPE of 30.82, the ten-year expected total return is 2.35%. The yellow box highlights the ensuing ten-year total returns for each monthly instance CAPE was over 30.

S&P 500 Total Annualized Return per CAPE

Now consider the Treasury yields are about 4%. Such a yield provides investors with an alternative that was unavailable over the last 15 years.

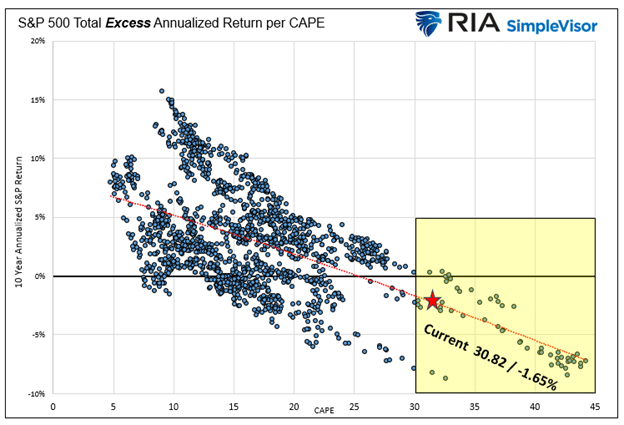

The following graph helps appreciate the tradeoff between the potential range of returns graphed above and the ten-year yields one could have locked in each time the CAPE valuation was over 30. The plot is similar to the one above, except the returns are presented in excess of ten-year U.S. Treasury returns.

CAPE Expected Excess Returns

Over the last 150 years, investors faced with CAPE valuations over 30, as they are, were almost always better off buying the ten-year U.S. Treasury.

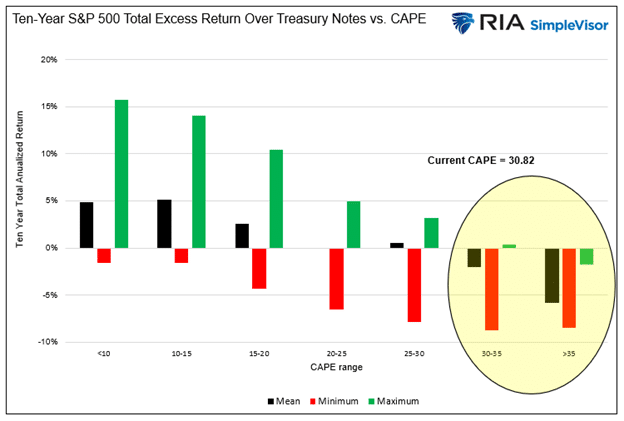

The bar chart below summarizes the scatter plot above to help highlight the point.

CAPE Expected Excess Returns

History says to take the bonds and run!

John Hussman Add His Two Cents

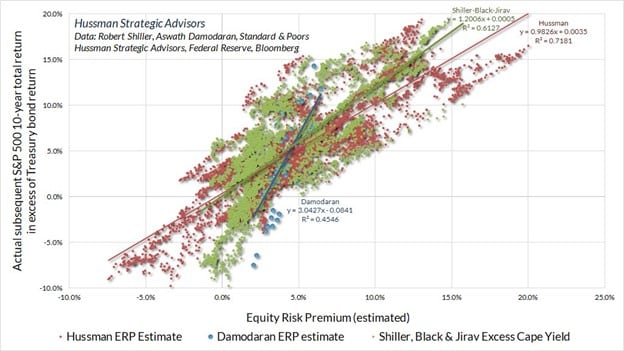

John Hussman’s graph below compares three equity risk premium calculations instead of CAPE to the subsequent excess returns. His analysis is more bearish than our CAPE-based expectations.

Hussman Expected Returns

With the current equity risk premium below 1%, long-term investors best take notice.

The Fly in the Ointment

After that bearish discussion, why not buy bonds and sell your stocks? Why not set it and forget it?

While the analysis is very compelling, it’s also flawed. For instance, if the market corrects over the next year by 40%, its annual returns for the remaining nine years can be over 6%, yet still attain a near zero ten-year return.

Conversely, stock investors may earn much better than average returns over the next few years only to get hit with a substantial drawdown down the road.

The bottom line is that timing matters. Accordingly, a shorter-term technical and fundamental analysis should largely determine your current stock/bond allocation unless you are willing to ignore the markets for ten years.

Summary

History, analytical rigor, and logic argue that long-term buy-and-hold investors should shift their allocations from stocks toward bonds.

For all other investors, pay close attention to your technical, fundamental, and macroeconomic forecasts, as the outlook for stocks versus bonds over the next ten years is troubling.