Oil Will Be Home for Christmas

2022.11.23 10:36

[ad_1]

As a general rule, don’t trade on pre-holiday thin-liquidity sessions. There can be seemingly amazing opportunities, but the price can still get shoved in your face by whoever it is who feels like pushing markets around.

A prime example today is the energy market, where are down nearly 4% at this writing. Recently, energy futures have been regularly jammed lower overnight in low-liquidity conditions and then have recovered during the day.

There is a structural shortage of energy globally at the moment, and inventories are low…but the sentiment is also very poor, and as I’ve shown before, open interest has been in a downtrend for years – aggregate open interest in NYMEX Crude hasn’t been lower since 2012.

So, it’s a market ripe for pushing around, and the day before Thanksgiving is probably not the day to take a stand by getting long, even when the reasons given for the sell-off are nonsense.

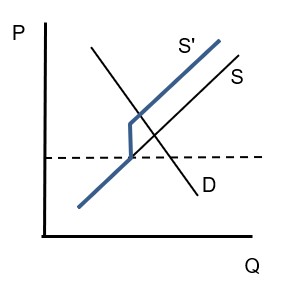

Today, the story is again about the price cap on Russian oil that is being implemented soon by the US and EU. Market participants seem to struggle with Econ 101 here. A price cap has one of two effects in the market under consideration: if the price cap is set above the market-clearing price, it has no effect. If the price cap is set below the market-clearing price, it leads to shortages as suppliers – in this case, Russia – won’t supply as much oil (if any) to the capped market when there are other uncapped markets (say, China and India). There is probably an area near the price cap where the cost of switching to delivering oil in other markets is higher than the gain from switching deliveries, but that’s only in round 1 of the game theoretic outcome.

In this case, since only the price from one supplier is capped, the result should be higher prices in the markets than otherwise since once the price exceeds the cap, one supplier is lost. The chart below shows the classic outcome. Below the cap, the supply curve is normal. Above the cap, the supply curve is left-shifted.

Kinked Supply Curve

This leads, at least in a frictionless market (which this isn’t), to prices being discontinuous around the cap. As demand shifts from left to right, prices behave normally and rise as they normally would until abruptly jumping higher once the capped producer is removed.

In any case, the price is more volatile than it would otherwise be. But, and this is important, it is never lower in a market where some or all of the suppliers are capped than it is in an uncapped market. At best, prices are the same if the caps aren’t in play. At worst, a combination of shortages and higher prices obtain.

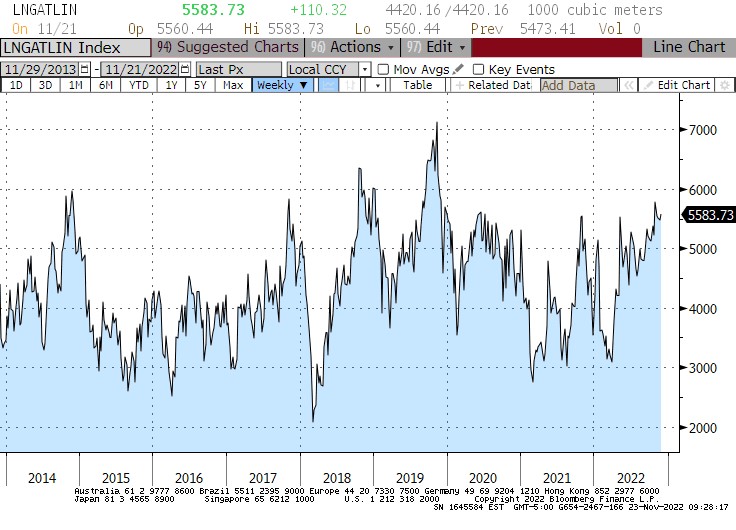

Speaking of shortages, it seems that people are growing calmer about the chances of a bad energy outcome over the winter in Europe. This seems, to me, to be related to the fact that inventories of gas are reasonably flush thanks to conservation efforts and vigorous efforts to replace lost Russian pipeline supply (see Chart, source Gas Infrastructure Europe via Bloomberg).

That’s great, but the problem is that since the pipelines are not flowing, Europe needs more gas going into the winter than they otherwise would have – because it’s not being replenished by pipeline during the winter, either. We certainly hope that Europe doesn’t run out of heat this winter, but the level of gas inventories is not exciting.

Putting downward pressure on both of these markets, but especially on Crude, is the idea that the world will enter a global recession in 2023. As I’ve been saying since early this year, that’s virtually a sure thing: we’ve never seen interest rates and energy prices rise this much and not had a recession. But I have thought that the recession would be relatively mild, a ‘garden variety’ recession compared to the last three we’ve had (the tech bubble implosion, the global financial crisis, and the COVID recession).

What worries me a bit is that the consensus is now moving to that conclusion. It seems that most forecasts are for a mild recession (although, predictably, economists are all over the map on depending on the degree to which they understand that inflation is a monetary phenomenon and not a growth phenomenon). I’m still in that camp, but that concerns me because the consensus is usually wrong.

[ad_2]

Source link