Inflation: Wars, Wars and More Wars

2022.11.22 10:20

[ad_1]

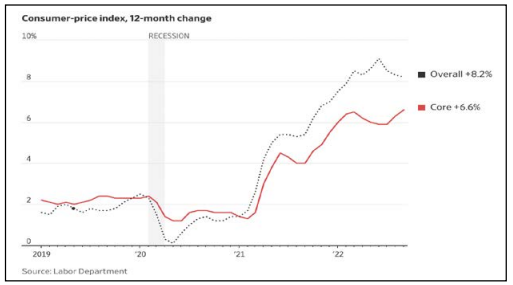

This month a cooling number sparked a mammoth rally on Wall Street on hopes that the Federal Reserve may be ready for a pivot (aka capitulation) in its battle against inflation. The gains are premature and won’t change the trajectory of the economy.

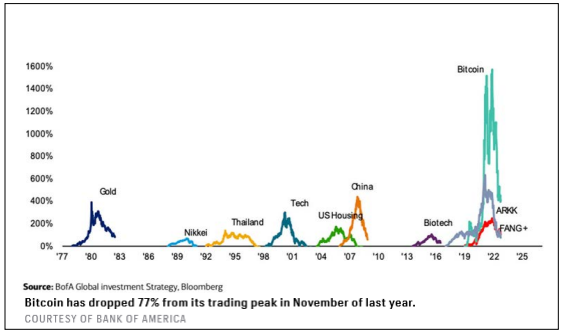

Bitcoin vs Gold Chart

Global inflation soared to 40-year highs from the monetary excesses of the past as governments unleashed trillions of dollars of additional spending, stoking the inflationary fires. Yet, despite the concern over rate increases, the global economy remains resilient. US households and companies are flush with cash from pandemic support packages. US capacity utilization are at 14-year highs. Q3 grew 2.6%. is back to pre-pandemic lows. Wages are up 8.2% fueling demand. Consequently with inflation so broadly based, investors’ hopes of a reprieve from rate increases will probably prove unfounded and yet another head fake or false dawn.

Also feeding inflation are wars. Wars cost money. They have substantial costs and have bankrupted nations. The US war efforts in Afghanistan, Iraq and Vietnam were debt financed, and those war debts and free spending governments produced more inflation, made worse by the pandemic stimulus. The decades of unfunded deficits, quantitative easing, and trillions of public spending created a faux sense of prosperity made possible by artificially low interest rates and cheap credit. At the same time central banks led by the Fed kept rates near zero using experimental techniques to revive inflation. It worked. But the corresponding boost to debt and consumption also created the biggest stock market bubble in history. The Fed’s free money sent a behavioral incentive to markets that not only money was free, but risk too was free. The FTX crypto pyramid implosion could put a $10-50 billion hole in the market. However, the mirage vanished when Biden’s colossal spending, the war and state intervention let inflation get out of hand forcing the Fed to crank up interest rates to tame inflation. And now investors must deal with both a raging war, soaring prices and skyrocketing interest rates deepening the financial hole between government expenditures and revenues. However deficits financed by new borrowings cannot go on forever as the UK discovered when they announced tax cuts, triggering a near collapse of their pension funds.

The problem is that consecutive budget deficits of 10% plus of GDP financed when money was cheap allowed governments to spend without repercussions. And governments kept on spending, funded by the central banks’ purchases of government debt leading to the inflation of today. First, the pandemic and now the Ukraine war. Tomorrow might be the need for more spending to boost an economic recovery to offset the soaring cost of scarce energy, food and credit.

The End of Cheap Money

Money is now expensive and dear. The important point though is amid this feast to famine, little was done to boost supplies and less to control out-of-control spending to stop fueling inflation. And today’s inflation is more than the cost of energy or food.

Inflation is simply too much money chasing too few goods. Inflation is high because spending has remained high and monetary policy too loose. History shows that money is the clear root of inflation, aided by spendthrift governments and complicit central banks. Economist Milton Friedman once observed that inflation, “is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon”, as part of the centuries-old quantity theory of money that holds prices are linked to the growth in money. Once believing that inflation was a transitory phenomenon, central banks now face problems putting the inflation genie back in the bottle. Most investors blame the adverse effect on Russia. Others fear rising rates will trigger a debt avalanche and the end of the long boom. The main culprit was the generous government spending on the pandemic, war, climate change and handouts aided by their central banks’ toolbox of experimental quantitative easing and outright purchases of $15 trillion of their own debt. Now that inflation is surging, central banks who earlier believed it was transitory have turned the screws on the global economy to tame an inflation that has become deeply entrenched and persistent.

Having misread inflation, policymakers are now misreading its causes. And as runaway inflation sends rates higher, markets are straining at the seams as we face a liquidity crunch in financial markets that has already caused a change in the UK government and now a crypto implosion. The stock market is in trouble because the bond market has already crashed. This is just the latest in a string of liquidity problems and as the liquidity swamp drains, only the ugly frogs are left, a harbinger of what is to come.

You Can’t Suck and Blow at The Same Time

Fiscal and monetary policy are related. As inflation rages and a deepening recession looms, the market hopes that governments will again succumb or pivot back to their free spending ways to avoid a UK type crash. That was the path in the 70s when deficit financing to fight the Vietnam War and President Johnson’s War on Poverty, unleashed double-digit inflation. Then the oil embargo hit. After hiking rates in the wake of serial commodity price shocks, policymakers prematurely declared victory over inflation when they saw the economy weaken and slashed rates. But those inflation embers grew to a fire, needing inflation-busting Fed Chair Paul Volcker to raise rates to double-digit levels which caused two recessions to bring inflation from 20% to 3.5%. Forty years on, the latest cycle is no different.

The out-of-sync conflict between fiscal and monetary policies is also being waged elsewhere. In Europe, pandemic support already cost half a trillion euros with the Italian government spending 11% of GDP and the French 10% of GDP. So far the politicians’ solution to rising prices is the introduction of massive subsidy support programs, windfall taxes, cheap loans and price caps costing some half a trillion dollars of public funds which stretches already tight sovereign balance sheets. The situation is dangerous.

With the US government debt topping $31 trillion and annual trillion-dollar deficits, the Treasury has to issue and refund debt at a whopping $5 trillion a year, forcing the central bank to print money to pay for America’s bills, contributing to solidly entrenched inflation as too many dollars again chases too little supplies. The Fed is in a box as fiscal policy pushes in the opposite direction of monetary policy, undermining the central bank’s effort to curb inflation. The yield on benchmark Treasuries jumped the most since the pandemic. Without both working together to squeeze inflation, history shows that you can’t suck and blow at the same time. In previous high inflation periods, the common denominator was this lack of both a monetary policy anchor and a sufficiently credible central bank response which resulted in the lack of monetary coordination. Faced with the resultant spiral in decades-high inflation and sinking markets, some central banks have already pivoted, reversing course, relaxing monetary policy in a repeat of yesteryear. Canada has slowed its rate increases and European politicians, fearful of their jobs have stepped up spending in defiance of their central banks amid signs that investors are getting more nervous about the limits of fiscal deficits, particularly following the turmoil that engulfed the UK debt market. Volatility leads to more volatility. The increased volatility is due to a series of events as countries discover that “exiting” or so-called quantitative tightening (QT) is not so easy. Governments haven’t got the message, particularly in America where the midterms were accompanied by extra rounds of spending. If the UK can so easily botch its “exit”, what is to happen with the United States?

CPI, 12-Month Change

Chickens Come Home to Roost The first casualty is Japan, which spent $60 billion in FX markets for the first time since 1991 to defend a collapsing yen that fell to its lowest levels since the seventies, aggravated by the Bank of Japan’s refusal to move rates in line with the global community. In maintaining an ultra-loose monetary policy, they hope to postpone the day of reckoning. Not so lucky was UK’s Liz Truss who quit in reaction to her mini-Budget’s deficitfinanced tax cuts which triggered a conflict between a lax fiscal policy and a tighter monetary policy. Her “tough” stance did not last long as both the Bank of England and government capitulated in a policy U-turn and re-instituted quantitative easing by buying $65 billion of government debt to save their pension funds that will drive inflation and interest rates higher. Truss served the shortest serving ever in office for a British prime minister, burying a queen, the pound and her government in only 45 days.

We recall in 2013, the Fed similarly tried to tighten but “pivoted” when global markets nosedived in a “taper-tantrum.” A looming source of trouble today is the Fed’s quantitative tightening (QT) to reduce the $9 trillion balance sheet which has quadrupled from a decade of bond purchases, increasing the supply of money and now playing an outsized role in the opaque $24 trillion Treasury market. However this time in removing $95 billion a month liquidity from the market, the Fed’s taper is made more difficult because of the book losses of $1 trillion against a paltry $42 billion of the Fed’s capital, requiring more accounting creativity. Normally, they could always print more, or can they? US broad money supply has shrunk from 30% to only 1% in the six months to July. In the UK, the government had to transfer $12.4 billion to cover the Bank of England’s red ink in its bond buying program. We believe that unlike the global financial crisis of 2007-2009 when over-extended financial institutions failed, this time it is sovereign governments’ turn as a game of chicken plays out between “independent” central bankers and their free spending elected officials.

Energy Geopolitics Boosts Inflation

Amid the energy crisis sparked by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, prices skyrocketed as Putin squeezed supplies to force the EU to abandon Ukraine. The surging energy costs created the biggest shock to the global energy infrastructure since the oil embargoes of the seventies. The brutal invasion only accelerated secular inflation as soaring prices caused demand destruction and energy-saving ways. Governments reacted with handouts, windfall taxes and massive interventions with average energy bailouts at 5% of GDP, declaring an energy war in addition to that other war where checks and spare tanks were being shipped to Ukraine. Today there are no winners, only losers in a war without end.

Things could get worse before they get better. The EU previously relied on Russia for close to 40% of its gas and more than half its coal and as a result, industries from fertilizer producers to steel makers to glass makers had to shutdown, unable to pay increased fuel bills. The EU is set to ban imports from Russia. Although America is one of the world’s largest oil producers at 11.4 million barrels of oil, they are also the largest consumer of some 20 million barrels a day, leaving them exposed since they must import some 8 million barrels of oil and petroleum products. Price caps or windfall taxes will only drive energy investments to other lower taxed jurisdictions, while robbing OPEC Gulf countries of revenues. US wholesale natural gas is up 68% this year. Any cap or windfall tax on one market such as Europe would send energy to other markets like Asia, risking a “beggar-thy-neighbour” conflict. Similarly Norway’s blockage of electricity exports or Germany’s purchases of scarce LNG supplies underlines the need for EU unity. Part of the problem is that Europe’s energy market is not a unified bloc but consists of 27 energy “private” fiefdoms.

The world’s fourth biggest economy, Germany built its mighty industrial complex on cheap Russian gas and that reliance backfired, as surging energy costs curtailed consumer spending, forcing factories to curb production. As de-industrialization set in, Arcelor Mittal, one of the largest steel complexes in the world will shut down two important mills. Germany has scrapped its fiscal austerity and has had to borrow a gorilla-sized $200 billion energy support package or 5% of GDP to help their citizens survive the gas crisis, violating EU’s solidarity in a return of realpolitiks. Germany once relied on exports to provide growth, but the war, higher costs for energy and China’s lockdown has removed an important prop to Europe’s economy. Who will replace Germany?

The US is vulnerable as the oil industry could not replace shortages at a time when the oil taps were needed to be turned on. At the same time to push gasoline prices down ahead of the midterms, Biden dumped a couple hundred million barrels of oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve which is at 38-year lows. In defiance of Washington, Middle East players have accepted renminbi and OPEC (including Russia) cut back output by 2 million barrels a day to boost oil prices, moving away from long time Western allies with the setting up a Petro-bloc along with an Asian bloc, upending the world order. Consequently, energy has become a pawn with negative economic spillovers, further enhancing inflation.

Climate Change Compounds Uncertainty

The new reality is that decarbonization itself is inflationary. Borrowings to finance energy subsidies, fuel rebates and caps might soften the near-term impact from inflation, but the underlying debt is a primary cause of inflation. We are not yet predicting hyperinflation but like the seventies, the causes and effects are eerily underway. And amid fast-changing climate changes, the world has never been so imbalanced with poorly allocated credit and unintended consequences. Mr. Biden’s ramping up of climate change expenditures hurt him in the midterms and exacerbated inflation by shutting down fossil fuels which accounts for some 80% of America’s usage. And despite higher prices, US oil industry output has flattened due to overregulation and the lack of investment after the Biden administration’s war on fossil fuels stopped pipelines and canceled oil leases. History shows that the conflict between the central bank and government is a dangerous step that has often triggered hyperinflation spirals in the past.

In addition to energy, the Russian invasion exposed the globe’s vulnerability to the availability of agriculture and water in the face of a dangerous combination of war, drought and higher prices for food and fertilizers. Without co-operation there is that other war of climate change. The decoupling between China and the US has implications for climate change as both countries are responsible for over 40% of global emissions. A growing population in the developing world has caused a decline in arable farmland colliding with precarious water supplies, such that agriculture like energy has been weaponized. Plant-based proteins have gone to a premium. And a global drought has taken down hydropower from California to Chile, driving up prices. Ironically one of the unintended consequences of the lack of water is that coal consumption has increased 6% as utilities try to maintain electricity supplies. Moreover decarbonizing our power grid whilst boosting infrastructure to meet increased demand from the electrification of energy for cars to steel mills can no longer be kicked down the road, yet another boost to inflation.

John’s Gold Report (click here for full report)

[ad_2]

Source link