How Long Can Fed Sustain the Unsustainable?

2024.07.13 14:58

As quoted below from an executive summary of a joint report by the Department of Treasury and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), the current deficit policy is deemed unsustainable. However, they fail to mention how long the Fed, via fiscal dominance, can sustain the unsustainable.

“The debt-to-GDP ratio was approximately 97 percent at the end of FY 2023. Under current policy and based on this report’s assumptions, it is projected to reach 531 percent by 2098. The projected continuous rise of the debt-to-GDP ratio indicates that current policy is unsustainable.” – Financial Report of the United States Government -February 2024.

Fed speakers will deny any notion that its monetary policy aims in part to help the government fund her debts. Regardless of what they say, we are already in an age of fiscal dominance. Monetary policy must consider the nation’s debt situation.

Fiscal Dominance

Fiscal dominance is a condition whereby the amount of debt in an economy reaches a point where monetary policy actions must allow Federal debts and deficits to be serviced and funded cost-effectively. By default, such monetary policy decisions will often come at the expense of traditional employment and price goals. As a result, the Fed must further distort the price of money and ultimately lessen the wealth of the nation’s citizens.

The age of fiscal dominance is here. Consider the following paragraphs and graph from our article Stimulus Today Costs Dearly Tomorrow.

A lender or investor should never accept a yield below the inflation rate. If they do, the loan or investment will reduce their purchasing power.

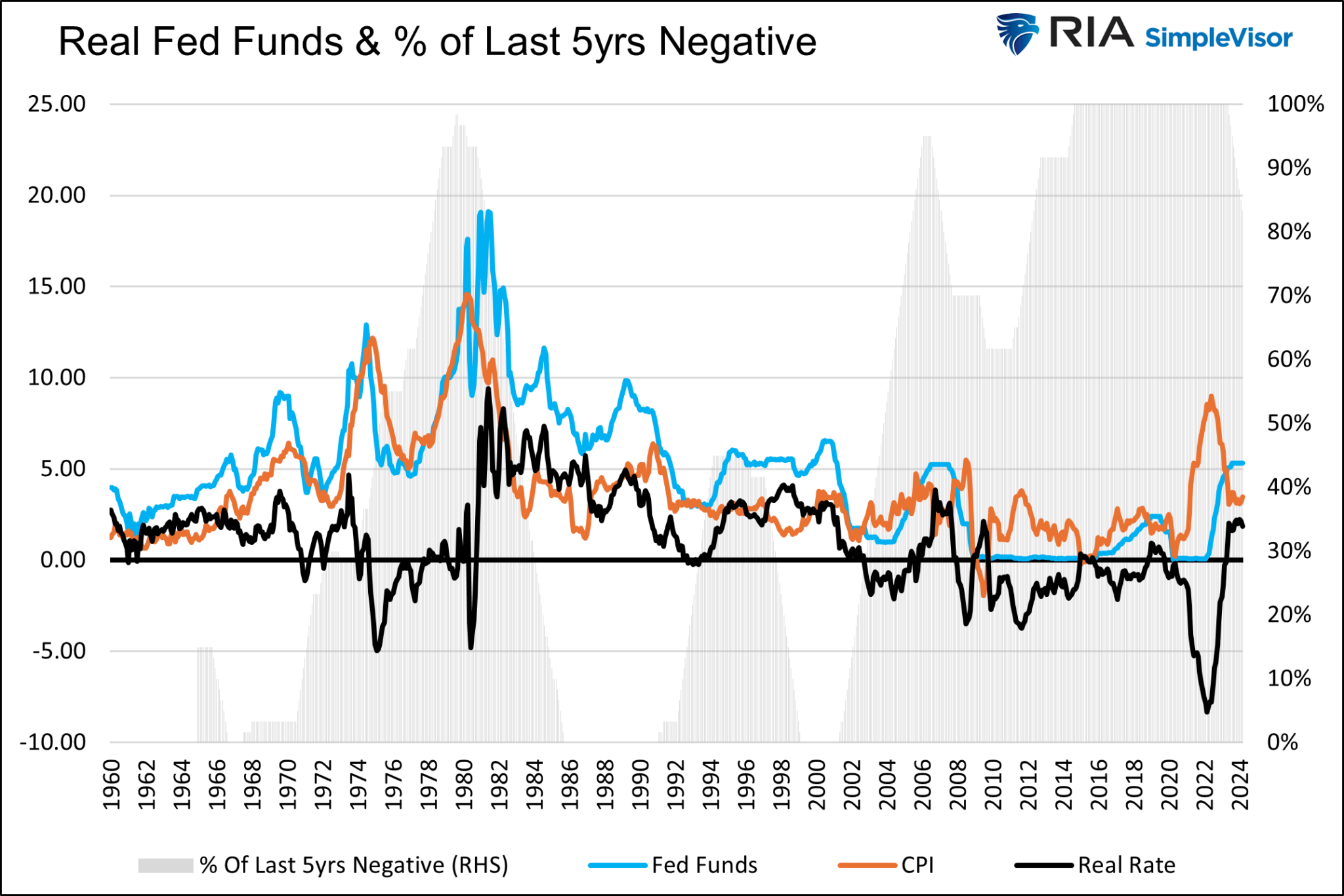

Regardless of what should happen in an economics classroom, the Fed has forced a negative real rate regime upon lenders and investors for the better part of the last 20+ years. The graph below shows the real Fed Funds rate (black). This is Fed Funds less CPI. The gray area shows the percentage of time over running five-year periods that real Fed Funds were negative. Negative real Fed Funds have become the rule, not the exception.

Soaring Debt Outstanding and Rising Rates

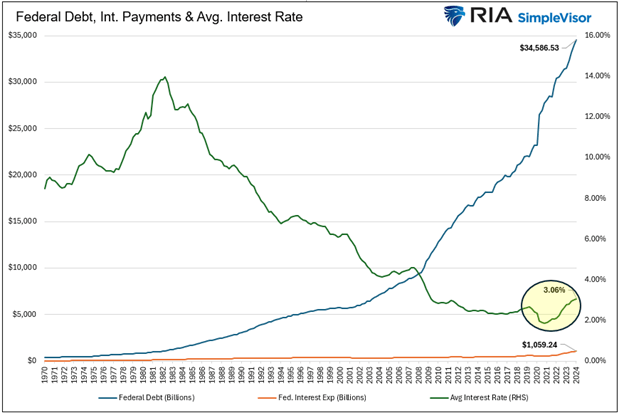

The government has added $2.5 trillion in debt over the last four quarters. Of that, over $1 trillion was to pay its interest expenses on the entire debt stock. Despite recent high interest rates, the average interest rate on the debt is still relatively low at 3.06%.

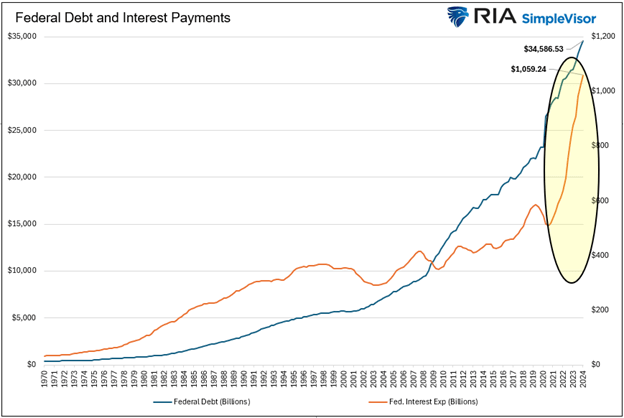

The two graphs below show why a relatively minimal uptick in the average interest rate on the debt is so troublesome. The federal debt (blue) has grown by 8.5% annually over the last ten years. Despite the amount of debt more than doubling over the period, the interest expense on the debt until very recently has remained very low. The first graph shows that the average interest rate increase is barely visible. However, the second graph shows that the rise in the government’s interest expenses is substantial.

As debt issued years ago with low interest rates matures and new debt with higher interest rates replaces it, the interest expense will keep rising. For context, if we assume the government’s average interest rate is 4.75%, likely close to their weighted average rate on recent debt issuance, the interest expense will rise to $1.65 trillion, not including new debt.

$1.65 trillion is over $300 billion above the government’s next largest expenditure, Social Security. Furthermore, it is double defense spending for 2023. The annual federal deficit has only been above $1.65 trillion twice (2020 and 2021) since its founding in 1776.

While the situation may sound gloomy, lower interest rates solve the problem. If interest rates return to the levels existing before 2022, the interest expense could easily fall below $700 billion, about half of the cost than if rates remain at current levels.

Therefore, interest rates will have to be kept in check by the Fed.

The Fed Understands Their Role

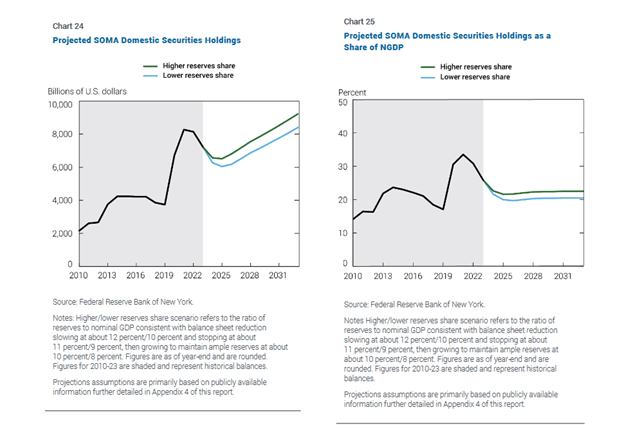

In 2008, Ben Bernanke said QE was a temporary measure that would be reversed once the economy and markets returned to normal. Trillions worth of Treasury purchases later, and the Fed now tells us it’s permanent. Consider the following graph and paragraph by the New York Fed.

“Under the two purely illustrative scenarios, the size of the SOMA portfolio continues to decline to $6.5 trillion and $6.0 trillion, respectively. The portfolio size then remains steady for roughly one year before increasing to keep pace with growth of demand for Federal Reserve liabilities, reaching $9.2 trillion and $8.4 trillion, respectively, by the end of the forecast horizon in 2033.”

The SOMA portfolio is the Fed’s System Open Market Account Holdings. This is the portfolio that holds bonds purchased via QE as well as its other monetary operations.

The graph on the left shows that the Fed expects the SOMA account to rise by about 40% starting in later 2024 through 2032. More importantly, the graph on the right shows that its increase will be commensurate with GDP. In other words, the Fed will continue to help fund the deficit by buying Treasury debt.

Monetary Policy

We know how QE and lower interest rates cut interest expenses, allowing the government to spend recklessly. However, there are other ways the Fed can supplement their efforts if needed. For instance, in our daily Market Commentary from April 24th, we shared the following:

If enacted, the new bank rules would force all banks to “preposition billions more in collateral” at the Fed to support future discount window borrowing. The article estimates that the Fed would require collateral matching up to 40% of a bank’s uninsured deposits, accounting for about 45% of the $17.5 trillion commercial bank deposits. Further, the new rules would require the banks to borrow from the window numerous times a year to help remove the program’s stigma.

In addition to bolstering the banking safety net, it would also force banks to hold significant collateral balances at the Fed. Collateral for Fed loans is quite often U.S. Treasury securities. Accordingly, this new bank rule is another way to help the Treasury fund its massive deficits and stock of outstanding debt from years past.

In late March, we shared another idea floating around Wall Street. Per our article QE By A Different Name Is Still QE we wrote:

Rumor has it that the regulators could eliminate leverage requirements for the GSIBs. Doing so would infinitely expand their capacity to own Treasury securities. That may sound like a perfect solution, but there are two problems: the banks must be able to fund the Treasury assets and avoid losing money on them.

The bank bailout BTFP enacted in March 2023 addresses the problems. As we wrote:

In a new scheme, bank regulators could eliminate the need for GSIBs to hold capital against Treasury securities while the Fed reenacts some version of BTFP. Under such a regime, the banks could buy Treasury notes and fund them via the BTFP. If the borrowing rate is less than the bond yield, they make money and, therefore, should be very willing to participate, as there is potentially no downside.

Summary

With the Fed willingly helping the government fund her debts, we believe the odds are small that any significant deficit reduction is possible. While the path is unsustainable, it is likely much longer than most pundits appreciate.

However, fiscal dominance comes with a significant cost. The Fed fuels the widening wealth gap by manipulating interest rates and indirectly influencing the stock market. As we have seen glimpses over the last five years, social unrest will likely become more prevalent. With that comes poor economic confidence from consumers and businesses, which in turn generates a headwind to the economy.

It’s not too late to try and fix our fiscal problems, but time is ticking.

As the saying goes, Rule #1 of holes: when you are in one, the first thing to do is stop digging.