Government Shutdown Risk Could Hamper Fed’s Fight Against Inflation

2023.09.20 08:49

It seems like ages ago that the US government flirted with a shutdown, but it was only this past spring when Washington danced on the precipice. A repeat performance is again approaching as political dysfunction in Congress leads to another game of chicken with a Sep. 30 deadline for passing a spending bill.

The threat is rising with each passing day as political warfare rages within the House Republican caucus. With just 10 days left to enact legislation, time is quickly running out for a solution. Despite the dwindling window of opportunity, Axios reports: “Most analysts seem pretty relaxed about the risks.”

“A government-wide shutdown would directly reduce growth by around 0.15 [percentage points] for each week it lasted; including modest private sector effects, the hit to growth could be around 0.2 [percentage points] per week. In the quarter following reopening, growth would rise by the same amount,” Goldman Sachs economists wrote in August.

“Shutdowns tend to be very short-lived and have a negligible impact on economic growth,” UBS fixed-income analysts wrote early this month.

Morgan Stanley last week published a similar outlook, advising:

“A government shutdown may cause only modest losses in gross domestic product (GDP)” and that “The 20 government shutdowns that have occurred since 1976 appear to have had limited impact on the economy.” History also suggests that a shutdown would be brief, lasting “on average… just over a week.”

The potential for a data vacuum for economic analysis, however, could be problematic. All the more so given this point in the business cycle, when the Federal Reserve is struggling to adjust monetary policy amid uncertainty about inflation and economic activity.

Greg Daco, the chief economist at EY-Parthenon, anticipates:

“A government shutdown would lead to a delay in economic data releases as agencies would suspend data collection, processing, and dissemination.”

In December 2018 and January 2019, the 35-day government shutdown led to a data drought with the postponement of over 10 key economic data releases including trade, housing and consumer spending data.

Given the current state of the economy and numerous uncertainties on the horizon, the absence of data could carry a significant cost for private sector economists, investors and Fed policymakers who would fly partially blind as they assess the US economy’s performance.

Agron Nicaj, US economist at MUFG, also sees trouble lurking if a data drought arrives.

“Decisions are made based on the consistency and reliability of government data,” he says. “This is especially true in today’s economic climate where uncertainty is high and the margin of error is very small for the Fed to over or under-tighten monetary policy.”

Although history suggests that a shutdown would be fleeting and the blowback minimal, some analysts think this time could be different.

“If there is a shutdown on Oct. 1, it could be quite long as there is not an action-forcing policy catalyst that would force lawmakers to find some common ground and pass a funding measure,” predicts TD Cowen Washington Research Group’s Chris Krueger in a research note. “The only politically sensitive deadline is Oct. 13, when paychecks are due to the uniformed military.”

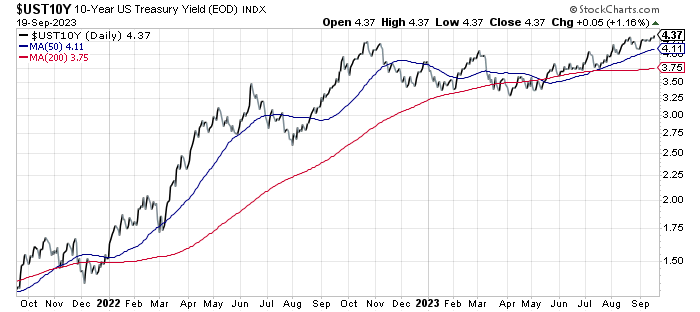

Meanwhile, the ticked up to a new 16-year high yesterday (Sep. 19), closing at 4.37%.

US 10-Year Yield-Daily Chart

US 10-Year Yield-Daily Chart

Later today, the Federal Reserve will what is expected to be a pause in rate hikes and a new set of economic forecasts, followed by central bank Chairman Jerome Powell’s .

The Fed is already in a tough spot as it grapples with the ongoing goal of taming inflation with minimal impact on economic activity. A government shutdown would make that job tougher and increase the risk of a policy mistake by pausing data reports from the government.

“If, for argument’s sake, the Fed overestimates the strength of the real economy and raises rates further in November — because of delayed downward revisions to July and August data, and delayed access to weaker September and October data — investors, businesses, and households could incur unnecessary costs and risks,” notes Julia Pollak, chief economist at ZipRecruiter.

“By the time the Fed discovered its mistake, the effects of excessive monetary tightening could be difficult to reverse.”