Food Inflation Served Hot and Cold

2023.05.04 17:01

Well, the Fed is done raising .

They aren’t quite done tightening yet, because the Federal Reserve is going to continue to shrink its balance sheet slowly. That’s important. The fact that the Fed is no longer hiking rates, but is continuing to normalize its balance sheet, is quietly impressive to me. It makes me wonder whether someone at the Fed understands that saturating the economy with bank reserves means that today’s tightening is fundamentally different from the tightening of yesteryear, which was a money phenomenon and not a rates phenomenon.

We may never know, but I do have to admit that Chairman Powell impressed me a little in his post-FOMC presser. Not impressed me like ‘he’s the greatest’ but impressed me like ‘this is what I’d hoped we were getting.’

I wrote back in 2017 that the fact he is not an economics PhD was a positive…although the fact that he did not know anything about macroeconomics before joining the Fed suggested that he has learned economics in an echo chamber from some of the most blinkered non-monetarists on the planet, whose main claim to fame is that their forecasts have been consistently, and sometimes colossally, wrong for a long period of time. Still, he has a different background and that always offers hope.

The conduct of monetary policy under Powell has certainly been different than it was under his predecessors. We have to give him that! In any event, he said several things that impressed me because they surprised me. I’ll have more details and specifics in our Quarterly Inflation Outlook released a few days after CPI this month.

But today, I’m here to talk about food inflation. Normally, food inflation along with energy is deducted from the to produce , which is more stable and therefore should give better signals with less noise as long as food and energy inflation are mostly mean-reverting. And normally, they are. Energy is famously mean-reverting; the nationwide average price of a gallon of gasoline right now is $3.574, which is down 5 cents from…April 2008. There is a lot of noise and not much signal, so it makes sense to deduct.

Similarly, food inflation has a large commodity component and is also very volatile. It is not as volatile as is energy, partly because we don’t consume most of the foods that we buy in pure commodity form but rather in a packaged form; also foodstuffs are much more heterogeneous than gasoline and so branding matters a lot. Still, the food component of CPI is pretty volatile and normally fairly mean reverting although unlike energy it definitely has an upward tilt over time.

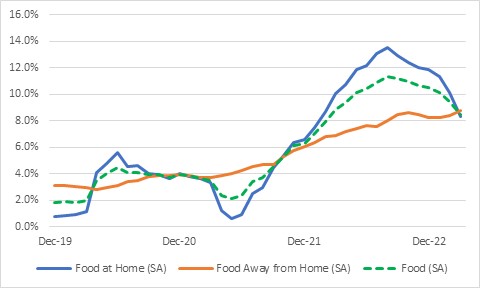

For some time now, though, food prices have been consistently adding to overall inflation. In mid-2021, trailing 12-month CPI for the “Food” subindex was about 2%; by late 2022 that was up to 11%! Recently, though, Food has started to come back to earth a little bit. The reason why is interesting and illuminating.

“Food,” which is 13.5% of the CPI, has two primary subgroups. “Food at home” is 8.7% of the CPI (about 2/3 of “Food”) and “Food away from home” is 4.8% of the CPI. The recent deceleration in the Food category has come entirely from “Food at home” (see chart, source BLS). That group got to about 14% y/y inflation, but most recently has fallen to a mere 8%. The steadier “Food away from home” is still plugging away, last at 8.8% y/y…a new high, actually.

Food CPI

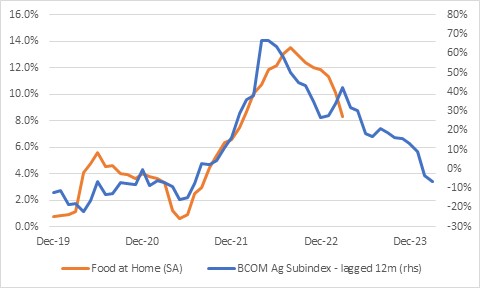

As you might expect, while “Food at home” does not directly track, say, wholesale cattle or wheat prices, persistent changes in commodities prices does eventually percolate into pricing. The following chart shows a very simple relationship between “Food at home” and the Bloomberg Commodity Index “Agriculture” subindex (which tracks the performance of , , , beans, bean oil, , , , and .

Aside from cotton, that list comprises a good part of what Americans buy to eat at home. So it isn’t terribly surprising that, at least for large movements in prices, these things eventually show up in the prices of things we buy. In this chart, the commodity index is lagged 12 months and shown on the right-hand scale. As an aside, consider how little of the price of what we buy must represent the actual commodity cost, if a 60% rise in commodities prices only results in a 14% increase in the price of Food at home, a full year later!

Food at Home Vs. AG Subindex

That chart says that “Food at home” should continue to decelerate and be a gentle drag for another year. On the other hand, “Food away from home” has completely different drivers that aren’t related to commodities prices hardly at all.

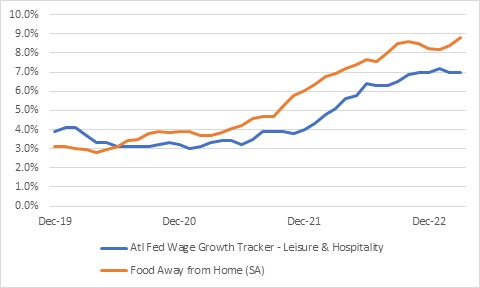

Atl Fed Wage Growth/Food Away From Home

In contrast to the prior observation, consider how much of “Food away from home” must be labor, if the correlation between labor inflation and “Food away from home” is so high and of such a similar scale. Of course, we know that to be the case: the labor shortage hit the restaurant industry very hard and those effects are still being felt. There is not yet any sign of a decline in wage growth among these workers, and consequently there is not any sign of a deceleration in inflation of “Food away from home.” It should continue to be additive to CPI for a while.

The dichotomy between these two parts of the “Food” category is, of course, exactly what concerns the Federal Reserve and other economists who examine inflation. I’ve written about it here (and spoken about it on my podcast) a bunch of times: core services ex housing is where the wage-price feedback loop lives. It’s where the persistence of inflation comes from, and that is why it is the Fed’s main focus.

Although I was writing about this before the Fed ever mentioned it, I have to give them credit – I thought they would seize on the fact that energy prices are pulling down overall inflation, or that rents may be decelerating soon, and use that as an excuse to take their usual dovish turn. They have not. The Fed actually seems to be focused on the right thing.

Maybe Powell is different, after all.

***

Subscribe at