FED, BoE, ECB: How Likely Are They To Fail?

2022.10.12 03:54

[ad_1]

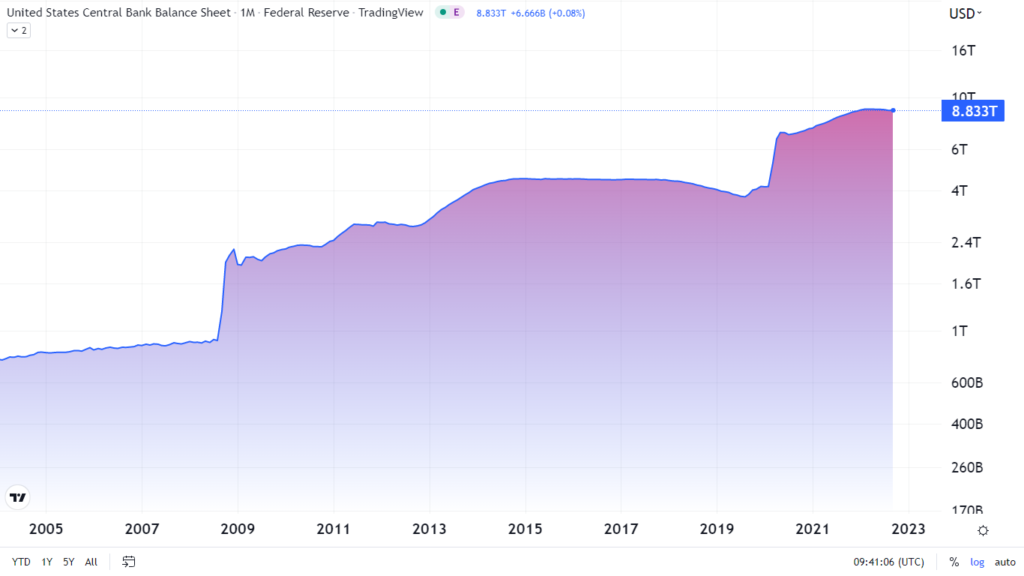

Quantitative Easing (QE) changed central bank balance sheets forever. In August 2007, the Fed’s balance sheet was about $900 billion, and this year peaked at $9 trillion. Within 15 years, its balance sheet rose ten times.

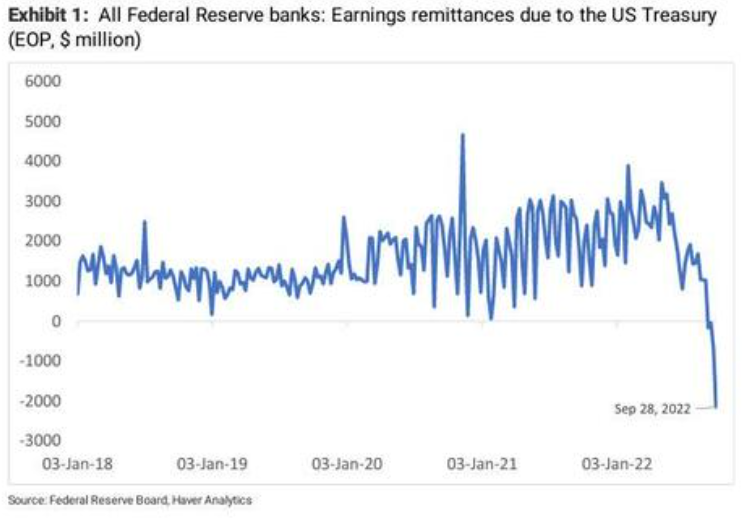

All revenues generated by the Open Market Account System portfolio, less interest expense, realized losses, and operating expenses, are remitted to the US Treasury. Before the Global Financial Crisis, these remittances averaged $20-25 billion a year, swelling to more than $100 billion as the balance sheet grew.

These remittances, though, reduce the deficit and borrowing needs. Net income depends on the (mostly fixed) average coupon on assets, the share of interest-free liabilities (physical paper), and the level of reserves and reverse-repurchase balances, the cost of which fluctuates with the policy rate.

Fed earnings remittances to treasury.

Fed earnings remittances to treasury.

From zero in 2007, interest-bearing liabilities have soared to nearly two-thirds of the balance sheet. The chart shows that the Fed’s net income has turned negative, and losses will deepen as the policy rate rises.

Because the Fed—like most central banks—does not mark its assets to market. Portfolio losses are unrealized and do not pass through the income statement. So, what do losses mean? Is capital affected? First, remittances to the government end, and the government issues more debt, according to Morgan Stanley.

The Fed then piles on its losses and, instead of reducing its capital, creates a “deferred asset.” When profits turn positive again, remittances remain zero until losses are made. Profitability will eventually return because the currency will continue to appreciate, reducing interest expenses, and QT will shrink interest-bearing liabilities.

BoE has an express indemnification agreement with the UK Treasury for losses from QE. The result is essentially the same as the Fed, but the political economy is different. Where the Treasury and the BoE share responsibility, the Fed stands alone.

Passive clearing for the BoE is difficult given the uneven duration structure of gold holdings, while the Fed has up to $95 billion a month being passively cleared. For the BoE, a one percentage point rise in Bank Rate cuts remittances by around £10bn a year, a significant amount for a country facing fiscal problems.

The proposal to reduce costs by prohibiting interest payments on reserves deserves careful consideration. Otherwise, the BoE will have to sell assets to regain monetary control, incurring losses.

ECB’s balance sheet is structured quite differently, but the logic is similar. The deposit rate will settle at 2.5% by next March, regarding the forecasts, implying losses for the ECB of around 40 billion euros next year. Bank deposits get the depo rate, which will be much higher than the portfolio yield.

In conclusion, Central bank losses matter, but only when they matter. They affect fiscal outcomes and may have political ramifications, but banks’ ability to conduct policy- like the definition of ‘’political economy’’ in the early 1900s – is not affected.

[ad_2]

Source link