Are Uranium Prices About to Go Nuclear?

2023.06.28 06:04

“This is the biggest moment for nuclear energy since the dawn of the atomic age.” – Maria Korsnick, President & CEO of the Nuclear Energy Institute, 2023 Nuclear Energy Assembly.

The investment case for uranium is nothing new. It has been around for some time now and over the past few years, a fairly rewarding trade at that. Of course, at the heart of the bull thesis lies the widespread adoption of nuclear energy given its viability as a key source of carbon-free base load energy, while being vastly superior to the renewable alternatives in nearly every way.

We are slowly but surely heading in the right direction toward a greater acceptance and adoption of nuclear energy. Unfortunately, any meaningful adoption of nuclear energy by the worlds policy makers will be a slow process, one that must be measured in years, not months. But, the signs are there.

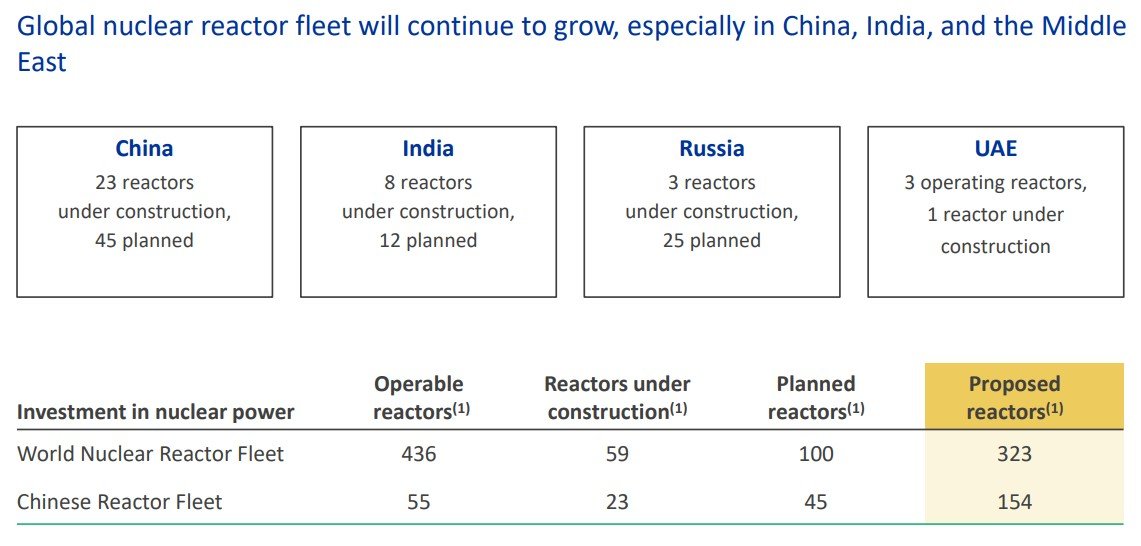

Source: Yellow Cake PLC

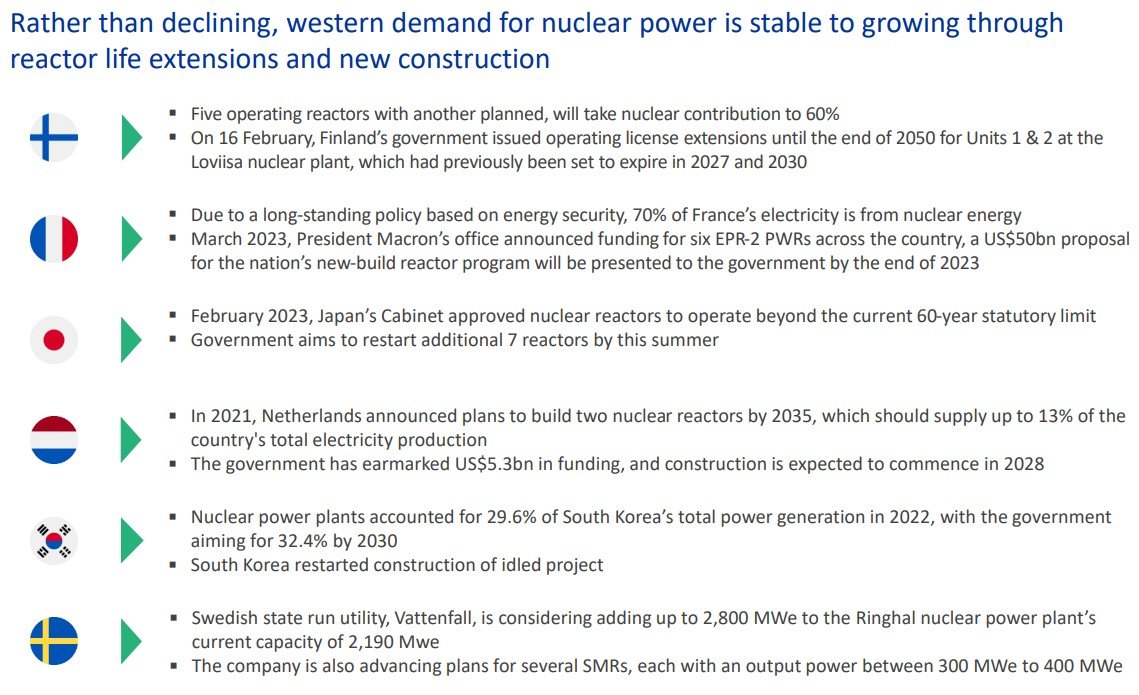

While much of the planned expansion in nuclear energy use is still predominantly from the East, Western countries are too slowly coming around. Sensibility can only be suppressed for so long.

Source: Yellow Cake PLC

Perhaps the most important of these developments is the pro-nuclear shift in Japan, home to the most recent nuclear incident that was Fukushima Daiichi in 2011.

While these developments are all positive, they are for the most part long-term dynamics which are unlikely to bear much fruit from an investment perspective over the next year or two. Fortunately, for investors looking to put capital to work in a timelier manner there are a number of dynamics within the uranium and nuclear energy space that could see prices of the former skyrocket well before widespread adoption of nuclear energy becomes commonplace.

A Story Of Supply & Demand

The beauty of commodities is they are driven almost exclusively by the interplay between supply and demand. is no different. It is through this imbalance that we could see prices rise dramatically not just in the long-term, but in the short-term too.

For much of the 2010s, uranium supply vastly exceeded demand and unsurprisingly, prices fell as a result. It wasn’t until the final years of the 2010s the market was able to work through the various sources of excess supply and glut in the market that we were able to reach a point whereby the next bull cycle could begin.

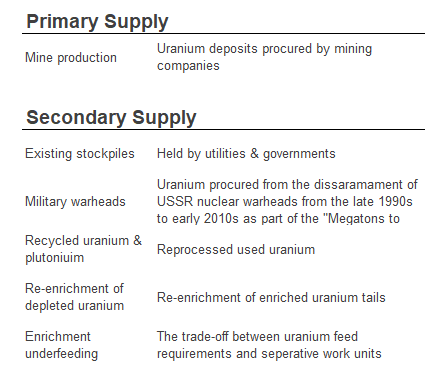

From the time uranium prices bottomed in 2016/2017 to the early 2020s, there was roughly 165 million pounds of uranium consumed annually. Uranium demand can be met from a number of sources, consisting of both primary supply and secondary supply.

During this period, mine production averaged around 140 mm pounds annually, while approximately 60 mm pounds pa of secondary supply came on to the market, primarily through drawdowns of existing stockpiles and via enrichment underfeeding (more on this later), as well as the re-enrichment of tails. Prior to 2013, secondary supply was also boosted by the “Megatons to Megawatts Program”, which involved the disarmament of USSR nuclear warheads. Given consumption of 165 mm pounds annually and primary and secondary supplies totalling ~200 mm pounds, this left around 35 mm pounds on average of excess supply that needed to be chewed through.

There are a number of dynamics at play here worth highlighting. First, during this period, primary sources of production (i.e. mined supply) of 140 mm pounds pa was below uranium demand of 165 mm pounds, on average. Thus, without these sources of secondary supply there would have been no deficit. What’s more, with nuclear sentiment seemingly taking a turn for the better and numerous nuclear projects coming back on-line, demand is set to rise meaningfully from here. Indeed, UxC estimates reactor requirements for uranium is set to climb to around 190-200 million pounds from 2023 onwards, up from the average of 165m pounds seen in recent years. As it stands, primary supply is ill equipped to meet such a rise in demand. 2022 production totalled only 129 million pounds according to UxC, compared to 123 mm pounds in 2021, despite the U308 spot price rising ~40% in 2021 and a further ~12% in 2023. This means, based on primary production versus demand, the market is currently in a deficit of around 60-70 million pounds. As secondary supplies are seemingly becoming less abundant by the month, this lack of primary production is key to the uranium bull thesis.

For Kazatomprom, the lowest cost producer of uranium, the marginal cost of production is around the $85/lbs level for U308. This is meaningfully higher than the current spot price of around $57/lbs.

Source: Kazatomprom

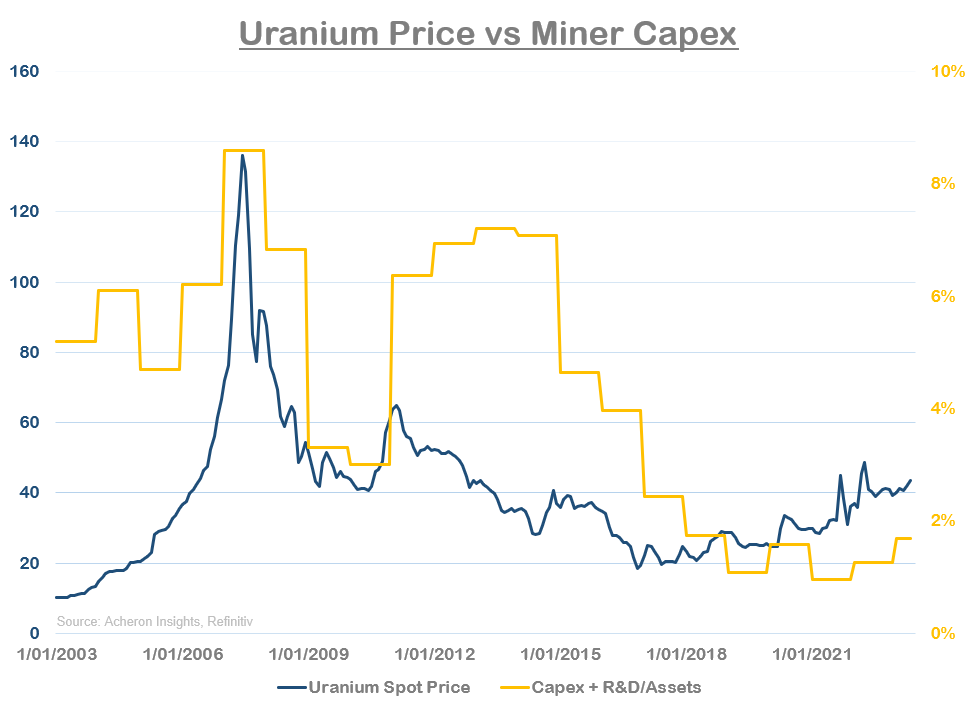

For many of the smaller uranium miners who have shut down production in recent years, spot prices at current levels are simply not going to incentivise enough production increases in the near future such that primary supply can ramp up to levels required to meet demand. This dynamic is only exacerbated by the fact that borrowing costs are their highest in decades.

Miners are under-capitalised, and under-capitalisation generally results in higher prices. There has been very little in the way of capital expenditure within the mining sector globally in response to higher prices so far amidst this cycle, with almost all capital expenditures undertaken in recent years being attributed to Kazatomprom, whose supply comes with a giant geopolitical asterix.

The bull market in uranium is simply a function of the capital cycle at play. Don’t get me wrong, supply will come back on-line at some stage as there is plenty of uranium out there. But mines can take up to two to three years for production to occur at scale, and we need higher prices to get us there.

A Reliance On Secondary Supply

While primary production has been far below reactor requirements for years now, this deficit has been met via secondary supply sources, and, up until recently, have actually been the primary cause of uranium oversupply.

It has taken the sector many years to work through the abundance of secondary supply. What we have seen is effectively a combination of the following:

- – Producers shutting down or reducing production and purchasing uranium via the spot market to meet their contractual requirements with utilities, as the cost of production exceeded spot prices.

- – Carry traders undercutting producers. This involved utilities sourcing their uranium needs by signing supply contracts with financial institutions rather than producers, who would then meet these supply needs by purchasing uranium in the spot market. This was beneficial for both utilities and traders as spot prices were below those of long-term contracts on offer from producers, allowing traders to buy spot uranium, add on a premium for their efforts and then sell the uranium to the utilities. In a world of suppressed interest rates, financial institutions will do anything to make a buck, and this went a long way to help work through the surplus above ground supplies. Now, with interest rates much higher, carry trades such as this are far less common.

- – Utilities and governments drawing down their own stockpiles and inventories to meet their reactor requirements. This has been the most obvious and important source of secondary supply. But, due to the opaqueness that is common in the nuclear industry, commercial stockpiles are difficult to quantify with precision. But, many reasonable estimates by those with deep knowledge of the sector (such as Mike Alkin of Sachem Cover Partners), believe stockpiles have been drawn down materially and may be near levels that actually require re-stocking.

While these dynamics have helped chew through the roughly 30-35 million pound annual deficit the market has had to suffer through up until the last couple of years, another source of secondary supply looks to have also run its course, and could in fact be turning from price headwind to tailwind. This is the shift from enrichment underfeeding to overfeeding, an important part of the nuclear fuel cycle and one that is difficult for most to understand, but is perhaps the most important of them all.

From Underfeeding To Overfeeding

Secondary supplies have for years been the antithesis of the uranium bull story. Because of secondary supplies, the primary supply deficit has not mattered. While the world is almost certain to transition to nuclear energy over time, “over time” is not really an investment thesis. Assessing where we are heading over the next one to three years is more in-line with my investment timeline. The question is whether the supply and demand deficit is sufficient to push uranium prices higher during this time frame. This is where underfeeding and overfeeding comes in.

To understand underfeeding versus overfeeding, a basic understanding of the nuclear fuel cycle is required. In its most rudimentary form, the nuclear fuel cycle is this:

- – Uranium, is mined and extracted from uranium bearing ores, crushed and ground to form U308, or “Yellowcake”.

- – U308 is then converted into uranium hexafluoride, or UF6.

- – UF6 consists of two isotopes: U-235 and U-238. The majority of the worlds commercial nuclear reactors require UF6 uranium enriched in the U-235 isotope for their fuel. Natural uranium consists of roughly 0.7% of the U-235 isotope. As such, natural UF6 is then enriched from 0.7% U-235 to around 3-5% U-235. It is through this step in which underfeeding and overfeeding can occur, so for the purposes of supply and demand, this is perhaps the most important part of the nuclear fuel cycle.

- – Once enriched, the UF6 then goes through a deconversion and fabrication process before being used as fuel in nuclear reactors to generate power. Spent fuel is then stored, reprocessed or disposed of.

Source: EIA

When it comes to the supply and demand story, the enrichment step plays a critical role. Not all enriched uranium is created equally. The net amount of enriched uranium is determined via a combination of force and feed, which in turn is dependent on enrichment capacity.

This dynamic is complex and can be difficult to understand. From an investment perspective, all that is needed to be understood is this: when there is excess enrichment capacity (i.e. enrichment facilities are easily able to meet their contractual requirements of utilities/reactors), enrichers are able to turn to underfeeding. Underfeeding allows enrichers to still meet their contractual requirements of enriched uranium, but are able to do so by using less feed (i.e. un-enriched UF6). Enrichers can then pocket the excess feed provided to them for future use or sell this into the market as a source of secondary supply. You get out more than you put in. Simple.

For much of the past decade up until 2021/2022, underfeeding resulted in approximately 20-25 mm pounds of additional uranium supply annually, a significant number. As of today, this material source of secondary supply may not only be disappearing, but could well be in the process of reversing into an additional source of demand. That is, a shift from underfeeding to overfeeding as enrichment capacity becomes increasingly tight.

Uranium enrichment is a highly capital-intensive endeavour and recently has become strategically and geopolitically sensitive. There are only a limited number of enrichment facilities in the world, of which approximately 39% are in Russia, with the others scattered around Europe, Asia and the Americas. As such, there are significant geopolitical question marks around uranium enrichment given the US and Europe get around 25-30% of their enriched uranium from Russia. As Western utilities look to source their enriched uranium elsewhere, their choices are limited as there are only a small number of Western enrichers.

Source: World Nuclear Association

With demand for nuclear energy on the rise, we are seeing enrichment capacity become increasingly strained. As capacity tightens, enrichers need to increase the “feed” in the enrichment process, which means using a higher tails (i.e. waste rate) in order to meet demand. Over capacity leads to increased uranium requirements, and thus enrichers may be required to turn to “overfeeding”, and the same level of uranium feed no longer producers the same level of enriched uranium. You get out less than you put in.

Enrichment capacity can be measured via Separative Work Units (SWU’s). SWU’s are effectively a measure of how much work is required to to enrich uranium, and can be thought of as the cost of enrichment services. When the cost of enrichment increases, it becomes more economical for enrichers to use more uranium feed. Given the spot uranium price of ~$55 per pound and USD/SWU of around $120-130 (up significantly over the past 18 months), it seems a shift to overfeeding is well and truly underway.

Source: UxC via Nikola Galozi

If we do see a continued move from underfeeding to overfeeding, the previous 20-25 mm pound source of secondary supply will instead turn to an additional source of demand. In a market already in a deficit, a 40+ million pound swing could be overwhelming.

The Contracting Cycle Is Heating Up

It seems utilities are catching wind of these supply and demand dynamics. We are seeing a significant pick-up in long-term contracting during 2023 as utilities work to snap up as much guaranteed supply as possible. UxC recently noted that 107 mm pounds of U308 have been awarded under term contracts thus far in 2023, compared to just 125 mm for the entirety of 2022. Indeed, this year has been the highest uranium contracting year in a decade. While this trend is telling in itself, it is expected to pick-up materially as 2023 progresses and into 2024. Particularly so given utilities are still contracting below their replacement rate, that is, they are consuming more uranium than they have been contracted to receive from suppliers, and drawing down the difference from their inventories.

Source: Yellow Cake PLC

As secondary sources of supply becoming increasingly scarce, the urgency of US utilities to secure supply will only escalate as they maximise security of supply in an already tight market.

The Geopolitical Premium

Although there have been no official sanctions on Russian enriched uranium and the country has been honouring its legacy contracts with Western utilities to date, the stress caused from geopolitical and supply chain security aspects of the uranium market for the West is only just beginning. As I touched on earlier, uranium conversion and enrichment prices have more than doubled in 2022 as Western countries self-sanction and seek alternative sources of enrichment capacity elsewhere, shifting the market from underfeeding toward overfeeding.

It seems only a matter of time before the entire Russian nuclear fuel supply is cut-off completely from the West. In fact, a bipartisan bill to ban Russian uranium imports has recently passed the US House subcommittee and is presently in front of Congress. Appropriately named the “Reduce Russian Uranium Imports Act”, the intent of this bill is to remove any and all Russian uranium from the US market.

Given there are only a few Western enrichers at present and enrichment facilities are very capital intensive, it appears there will be a brief window where there is insufficient enrichment capacity to meet Western demand before sufficient non-Russian enriched uranium enters the market. Should this indeed be the case, higher prices would likely result.

Financial Buyers Could Corner The Market

While the supply and demand story alone is seemingly favourable, what makes this investment thesis all the more attractive are the workings of a number financial entities involved in the uranium market. We could see a situation where these financial players corner the market and provide reflexive price action to the upside.

The big name here is the Sprott Physical Uranium Trust. Previously the Uranium Participation Corp (UCP), Sprott Asset Management took over control of the trust in September 2021. While the original purpose of UCP was to hold physical uranium on behalf of investors (to which it acquired roughly 18.5 mm pounds over its lifetime), upon its takeover Sprott converted the entity from a corporate structure to a trust structure, and renamed it the Sprott Physical Uranium Trust (U.UN). Better known as SPUT.

Since the takeover, the impact on the physical uranium market has been significant. Because SPUT is a closed-ended fund, this means when it was initially created only a fixed number of shares were issued to the open market. These shares are now openly traded and like all closed-ended funds, can fluctuate from a discount to premium to net asset value (NAV). SPUT’s closed-ended trust structure allows the fund to issue additional units onto the market when it is trading at a 1% or greater premium to NAV via an At-The-Money offering, to which it can use the proceeds to purchase additional physical uranium.

From late 2021 to mid-2022, SPUT was trading at a significant premium to NAV (and has fluctuated between premium and discount since), allowing it to issue additional shares and thus purchase a total of 43.5 mm pounds of physical uranium.

Source: Sprott Asset Management

In a market that is already in a deficit of approximately 15-30 mm pounds annually, the introduction of such a financial player with the ability to remove material amounts of physical uranium from the market is significant. Importantly, SPUT is not able to sell its physical uranium, and when the listed price trades at a discount to NAV (as it does currently), those pounds it has sequestered from the market remain in storage.

It doesn’t end there. In addition to SPUT, there are a number of other physical uranium trusts that have recently been created or are in the process of being created. In 2018, a similar vehicle listed in London by the name of Yellow Cake (YCA), which itself has since purchased roughly 20 mm pounds of physical uranium. YCA has a contract in place with Kazatomprom to acquire up to an additional US$100 mm worth of physical uranium annually through 2027.

Elsewhere, another entity is in the process of launching in Switzerland named the Physical Uranium AMC. Managed by Zuri-Invest AG, this fund will invest in physical uranium on behalf of “qualified, institutional and professional investors”, and is in the process of raising around US$100 mm (there are rumblings this fund has undertaken a material amount of buying of physical uranium in recent weeks, and has perhaps been largely responsible for the recent move higher). Kazakhstan also recently launched a similar physical uranium investment vehicle, while there are rumours of several more on the horizon.

Importantly, the introduction and involvement of these financial players increases the vulnerability of the physical uranium market, adding to the risk whereby they corner the market and see prices appreciate much higher than they perhaps should. As prices rise and investor speculation returns, these financial players provide another layer of incremental demand which a market already in deficit cannot support.

Market Technicals

From a technical perspective, it is hard not to appreciate the chart of uranium or any of its miner or physical fund derivatives. Take SPUT for example, aside from the Russia-Ukraine war induced temporary spike in early 2022, clear overhead resistance has been established at the $18 level, while we continue to see higher lows being made. It seems only a matter of time before this level is broken, which could usher in the next leg higher.

Uranium Prices Could Go Nuclear

In summary, not only does the long-term outlook for uranium appear attractive from a supply and demand perspective, the shorter-term dynamics at play also suggest material upside could be on the cards sooner rather than later. The secondary supply dynamics which have been such a significant headwind for prices over the past decade appear to be dwindling as inventory drawdowns become exhausted and we seemingly shift from underfeeding to overfeeding. In addition, we have a clear primary supply deficit, supply chains with geopolitical risks and a financial entity potentially cornering the market. All told, this is a market with a deficit of anywhere between 15-30 million pounds pa and counting. It may not be this month or even this year, but one day soon prices will need to adjust to this reality.