U.S. Dollar Likely To Consolidate In October

2022.10.03 16:55

[ad_1]

The historic rally accelerated in September. By some measures, it is as rich as it has been in the half-century since the end of Bretton Woods. Persistent price pressures, a robust labor market in many dimensions, and the Federal Reserve’s latest forecasts warn that financial conditions will tighten into next year. However, we suspect that the market may have seen peak Fed hawkishness when it briefly priced in a terminal Fed funds rate of around 5.50% towards the middle of the next year. As September drew to a close, the market had re-adjusted and returned to about a 4.50% peak rate by the end of Q1 23. After dramatic gains in September, we anticipate a corrective/consolidative phase in October for the dollar.

The moves of the nominal exchange rates, as momentous as they may be, might not capture the magnitude of the overshoot that is taking place. According to the OECD’s measure of purchasing power parity, the and are at historic under-valuation levels of almost 45% and 44%, respectively. is nearly 30% undervalued. Consider that the major currencies rarely deviate more than 20% from the OECD’s fair value (PPP). In the past, such an over-valuation of the dollar would spark concern by some US industries of unfair advantage to European and Japanese producers. Some multinational companies cite the decline in the dollar value of their foreign earnings, but the broader pushback has been minimal.

US goods exports reached record levels in July despite the dollar’s strength before slipping slightly in August. More and higher priced energy shipments have made up for slower growth in other goods shipments. Imports fell for five months through August and are off 6% from the record high set in March. This sucks away some of the oxygen of potential protectionist sentiment that has been heard in past periods of solid dollar appreciation.

Unlike the last big dollar rally in the mid-1990s, when then-Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin initiated the firm dollar policy, the current administration has been reluctant to resurrect the language. Some feared that it had lost its meaning and/or was confusing. However, the strong dollar policy is alive and well at the Federal Reserve. The dollar’s strength is understood to be one of the channels through which the rate hikes tighten financial conditions, which in turn is to help bring demand back into line with the supply constraints. As a result, US officials have shown little interest in a Plaza-like agreement (to drive the dollar down as in 1985) that some think is necessary.

Depending on where you sit, the Fed is either the hero or the villain of the bullish dollar narrative. However, there might be more to it than that. The eurozone and Japan are experiencing a dramatic deterioration of their external balances. Consider the recent trade reports. The eurozone’s average trade deficit in the first seven months of the year was 25.3 bln euros. For the same period last year, it had an average monthly surplus of 16.6 bln euros. In the Jan-July period in 2019, the average surplus was larger, near 21 bln euros. Japan’s latest trade figures cover August, and this year Japan has recorded an average monthly deficit of JPY1.53 trillion (~$11 bln). In the same period last year, it averaged a monthly surplus of JPY73 bln.

Without getting too far ahead of ourselves, the forces that will change this, even if it takes a bit more time, have been set into play. The price of money adjusts quickly compared with the price of goods, trade flows, and investment flows. The unprecedented extreme valuations will encourage a change in the behaviors of businesses and households. They will be part of the broader narrative when the (dollar’s) bull market ends.

In 2008, a famous fashion model demanded to be paid in euros instead of dollars. A rap artist featured euros in a video. The press and financial research were full of eulogies for the dollar. We suspect that type of extreme sentiment, but its opposite, is being seen now, with claims that there is no alternative to the dollar, Europe is “uninvestable,” or sterling is an emerging market currency.

Despite the US economy having contracted in H1 22, and the median Fed forecast chopped this year’s growth estimate to 0.2% from 1.7% in June, the US appears to be emerging from Covid, the energy crisis, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in a stronger position compared its allies and competitors. Yet, the insistence that cyclical forces are structural often seems to provide the last fuel for the move and, to mix metaphors, the last drop of tea that overflows the cup.

China is having a particularly difficult time. Most of it is homegrown. As Xi brought the tech giants to heel, the regulatory crackdowns used anti-corruption campaigns to get rid of opposition, coupled with the zero-Covid policy, have weakened the growth profile. In addition, its Covid vaccine was reportedly less effective than the ones more common in the US and Europe. The vaccination rate appears relatively low and slow to roll out boosters.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine also may be encouraging foreign businesses to re-think exposure to China. The UN report on Xingjian, human rights violations, confirmed what many suspected. The property market, a significant driver of economic growth and development, has been hobbled and is still bleeding. In this context, Xi is expected to be granted a third term at the 20th People’s Congress in mid-October. The PBOC has introduced measures meant to slow the yuan’s depreciation.

Among the G10 countries, Japan stands out. It still has a negative policy rate, and not only has it not raised rates, but Bank of Japan Governor Kuroda also insists that policy will not change soon. A few days after the BOJ increased its bond-buying (expanding its balance sheet), the Federal Reserve delivered the 75 bp hike. As a result, the dollar surged above JPY145, and the Ministry of Finance intervened to support the yen for the first time since 1998. However, the intervention did not meet the three conditions that would boost the chance of success: surprise, multilateral, and a signal of a policy change.

The BOJ policy appears riddled with contradictions, including adjusting the foreign exchange rate while fixing interest rates under Yield Curve Control. The intervention did stem the dollar’s appreciation but could not knock it below JPY140, which means that it was unlikely to have inflicted the kind of pain that would discourage further yen weakness. Volatility did not subside very much, either. Benchmark three-month implied volatility set a high before the intervention near 13.4%. It was near 12.3% at the end of September, which is still more than twice the year-ago level.

Japanese policymakers may have complained the most in the G10 about the dollar’s strength, yet even before the September 22 intervention, it was not the weakest or most volatile currency among the G10. By September 21, the yen was off nearly 3.5% for the month. The was off 3.7%, the was down almost 4.1%, and the had lost more than 4.3%. Sterling had traded at its lowest level since 1985, while the yen was at its weakest since 1998. The three-month implied volatility (embedded in option prices) for the yen on September 21 was 11.1%. The Scandinavian and Antipodean currencies were more volatile, and the euro’s volatility (10%) was not significantly different.

Aside from the Bank of Japan, central bankers have persuaded investors that the need to get inflation in check is the paramount objective, even if it means economic pain. As a result, higher interest rates and weaker growth are anticipated. However, the pace of tightening may moderate soon. Among the G10, both the Bank of Canada and the Reserve Bank of Australia have been explicit about this, and the Fed may have another 75 bp hike in it, but it too is seen slowing the tightening later in Q4.

The relationship between currencies and policy rates is more complicated than it may seem looking at the yen’s weakness. The Bank of England raised rates more than twice much as the Swiss National Bank. As a result, the Swiss franc eclipsed the Canadian dollar in September as the strongest major currency this year, and sterling is among the weakest. Sweden’s Riksbank delivered a 100 bp hike last month, and the krona sold off to new record lows.

The dollar rose against most emerging market currencies in September. The JP Morgan Emerging Market Currency Index fell by about 3.2% in September, which brought the year-to-date loss to 7.8%. The theme for most of this year has been the outperformance of Latin American currencies. It stalled in September. The posted a minor gain (less than 0.2%), making it the second best performer among emerging market currencies after the Russian rouble. Brazil, which had been a market favorite, succumbed to pressure ahead of the presidential election. Leaving aside the Hong Kong dollar, three of the top five performing emerging market currencies in Q3 were from Latam: Brazil, Mexico, and Peru.

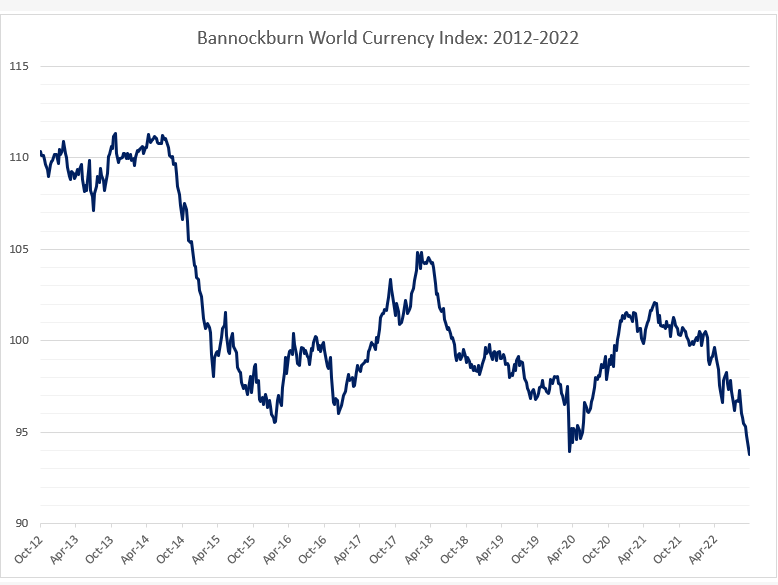

Bannockburn World Currency Index 2012-2022

Bannockburn World Currency Index 2012-2022

Bannockburn’s World Currency Index, a GDP-weighted basket of the currencies representing the 12 largest economies, fell slightly more than 2% in September as all but the Russian rouble and Mexican peso fell against the dollar. The BWCI took out the 2020 low. With a strong dollar, tighter Fed policy, and economic weakness in China, one may have expected emerging market currencies to have fared worse than the G10. Yet that is not what is happening. In September, the major currencies in the index fell by an average of 4.4% (excluding the dollar), and the emerging market currencies in the index fell by about 2.5%.

US Dollar

The labor market’s resilience boosts the Federal Reserve’s confidence to raise rates to bring inflation back to its target. Encouraged by the latest Fed projections, the market looks for a 75 bp hike in November to be the last of that size before slowing to 50 bp in December. Most of the heavy lifting will be done this year, but rates are expected to be hiked in Q1 23 when the market sees the peak. The Fed anticipates cutting rates in 2024 while the market continues to lean toward a cut late next year. Inflation may be near its peak, but rents and medical services will likely keep core inflation sticky. The dollar’s appreciation will reduce the value of foreign earnings for US multinational companies. Nevertheless, the dollar’s appreciation is one of the channels through which financial conditions are tightening. As a result, we expect the dollar to be more vulnerable as the end of the monetary cycle approaches.

Euro

The eurozone economy is on the edge of a recession. The energy shock and broader cost-of-living squeeze are taking a toll, yet with inflation at 10%, the European Central Bank has little choice but to continue to tighten policy. After a 50 bp hike in July, the ECB hiked by 75 bp in September, and it looks poised to deliver another 75 bp hike in October and at least another 50 bp move in December. Many eurozone members are trying to protect households and small businesses from the surge in energy prices. The euro’s decline exacerbates inflation, but the depreciation against the dollar overstates the case as the trade-weighted index has fallen by less than half as much. As widely expected, following the collapse of the Draghi government, Italy has elected among the most right-wing governments in modern times. The more conservative forces also won the Tory Party leadership contest and Sweden’s general election. In anticipation of rising tensions with the EU, the premium demanded by investors for Italian assets has risen sharply. ECB President Lagarde has been explicit that the new Transmission Protection Instrument will not be used to save countries from their policy mistakes. This will be a potential flash point in the period ahead.

Japanese Yen

The Bank of Japan increased the amount of 5–10-year bonds it regularly buys a couple of weeks before the Federal Reserve delivered a 75 bp hike and a hawkish message. Several hours after the FOMC meeting concluded last month, Governor Kuroda confirmed no change in BOJ policy. The dollar, which rose broadly after the Fed’s decision, was almost at JPY146 when the Ministry of Finance ordered intervention to buy yen for the first time since 1998. The operation drove the dollar a little below JPY140.50. While late yen shorts felt the pressure, the underlying drivers (policy divergence and a negative terms-of-trade shock for Japan)- and sentiment have not changed. We suspect the market wants to challenge Japanese officials. The key is still US interest rates, which might help explain the decision to intervene against the odds. Japan is playing for time: moderate the pace of decline as the peak in Fed policy and US rates are approached.

British Pound

The Bank of England was the first G7 central bank to hike rates (2021), but the aggressiveness of the Fed and other major central banks left it behind and contributed to the weight on sterling. However, the mini-budget delivered by the new government was panned by economists and snubbed by investors. Sterling dropped like a ton of bricks to a new record low of about $1.0350. UK interest rates soared. The Bank of England has signaled a significant rate hike when it meets next in early November. The swaps market has nearly 150 bp discounted. Worried about the twin deficits (current account and budget), interest rates soared in a destabilizing fashion that threatened financial intermediaries, like pension funds. The Bank of England stepped and bought bonds. This, and the promise to hold back from selling bonds, which it had planned to begin in October as part of the effort to unwind the balance sheet that had expanded during the pandemic. The sentiment is extreme, and several banks now see sterling breaking below parity this year or early next year. We suspect this will prove to be an exaggeration.

Canadian Dollar

The combination of the slowing of the Canadian economy and the drying of risk appetites (using the as a proxy) saw the fall out of favor. The Canadian dollar fell to new two-year lows last month. The economy’s outperformance in the first half is ending, helped by an aggressive central bank that surprised the market with a 100 bp hike in July and followed up with a 75 bp move in September. The swaps market anticipates a 50 bp hike in October and a 25 bp hike in December before the central bank pauses. The market looks for a terminal rate between 4.00%. This is to say that the Bank of Canada could be the first G10 central bank to reach its peak, possibly at the end of the year. The Canadian dollar’s exchange rate continues to be sensitive to the general environment for risk. Stability in the US equities seems to be a precondition for a Canadian dollar recovery in October. Otherwise, the US dollar looks set to test the CAD1.40 area.

Australian Dollar

The Reserve Bank of Australia delivered its fourth consecutive 50 bp hike last month to lift the cash target rate to 2.35%. The impact of the hikes is beginning to materialize, and Governor Lowe has suggested that the pace of hikes may slow. With the weakness of the and with most central banks still moving in 50-75 bp increments, the market still favors another 50 bp hike at the October 4 meeting (~60% probability). The terminal rate is seen around 4.00%-4.25% in mid-2023. Australia’s two-year yield approached a 100 bp discount to the US, double what it was at the end of August. Since the mid-1980s, it has only once traded at more than a 100 bp discount (May 2019). The Australian dollar has broken through our $0.6600 objective and dropped to about $0.6365 before recovering. It needs to resurface above the $0.6550 area to take the pressure off the downside, which could extend toward $0.6200.

Mexican Peso

The peso was bowed by the dollar’s surge last month. It still managed to eke out a minor gain The currency had been less volatile than several G10 currencies. There was a fear last year that President AMLO was going to stack the central bank with doves, but this proved wide of the mark. As the Federal Reserve turned more aggressive, so did Banxico, and its reputation enhanced. It delivered a 75 bp hike in late September to 9.25%. The swaps market sees the terminal rate between 10.50% and 10.75%. If Banxico matches the Fed, it could be at 10.50% at the end of the year. The peso is still among the best-performing currencies this year, and yields on hedged and unhedged basis look lucrative. The Brazilian real has fared even better for the year as a whole (~4% vs. .2%)). Lula is expected to be elected President even if it requires a run-off. He appears chastened, and investors seem to still feel comfortable that moderate policies will be pursued.

Chinese Yuan

China is one of the few countries easing monetary policy. The divergence of monetary policy goes a long way toward explaining the pressure on the yuan. At the beginning of the year, for example, China’s bond paid around 125 bp more than the US. Now, it is near a 100 bp discount. After trading broadly sideways in the first three-and-a-half months this year, officials accepted about a 6% depreciation of the . There was another period of stability from mid-May until around mid-August. Since then, it has taken another leg lower. Though the end of September, the yuan has fallen by about 6.0%. The PBOC has moved to moderate the pace of the descent by cutting reserve requirements on foreign currency deposits, discouraging speculation, and consistently setting the dollar’s reference rate below projections. The dollar is allowed to rise only 2% away from the fixing. Nevertheless, the divergence of policy can continue to weigh on the yuan. As the dollar pushed above CNY7.20 and as it probed the upper end of its band, the PBOC reportedly threatened to intervene directly in the foreign exchange market. The zero-Covid policy is taking a severe economic toll, and economists continue to revise down Chinese growth. Outside of the property market, the economy appears to be stabilizing, and the mid-September re-opening of Chengdu and Dalian may be reflected in next month’s data. Rather than having to explain it away, as Xi takes a third term, he might use the economic challenges as a stick to stir up nationalistic sentiment.

[ad_2]

Source link