Twenty years after euro “No” vote, Swedes fret over weak crown

2023.09.14 01:44

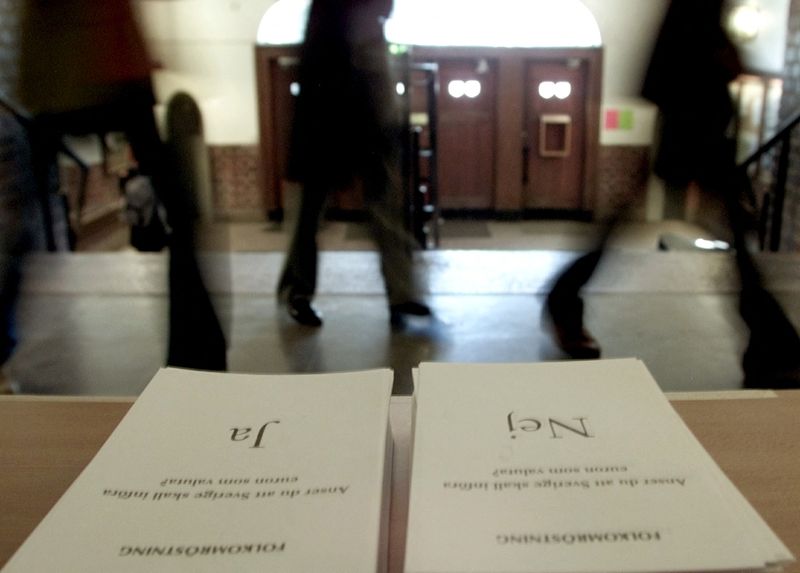

© Reuters. FILE PHOTO: People pass by ballot papers at a polling station in Stockholm during a September 14, 2003 referendum on whether Sweden should join the euro zone./File Photo

By Simon Johnson

STOCKHOLM (Reuters) – Need a cheap, reliable second-hand car? Think Sweden, where a nosedive in the local crown currency over the past 18 months is proving a blessing for used-car dealers and other exporters.

But 20 years after Swedes voted in a referendum to stay out of Europe’s single currency, the crown’s 17.5% slide against the euro is not making everyone happy. Many in a nation used to high living standards are being forced to tighten their belts.

“Many foreign car dealers think there is a sale on in Sweden,” Joachim Agren, senior key account manager at the Swedish branch of BCA, Europe’s largest vehicle remarketing company according to its website, told Reuters. He said overseas buyers now account for the majority of its sales at auction, doubling their 30% share of recent years.

Purchasing power abroad has tumbled with the currency. In the second quarter, Swedes were the 12th biggest buyers of property in Spain, according to Registradores de Espania – four places lower than two years earlier and behind the Chinese.

Companies like KP Energy, which imports solar panels to sell to trade buyers, cite the damaging effects of higher purchase costs and rising interest rates, which hit household spending.

“It impacts us a huge amount when the crown weakens against the euro and when the demand picture changes,” its CEO Filip Wiqvist said.

KP Energy had forecast strong growth this year after the market doubled in size in 2022. Now, it expects a contraction, even with Sweden and the European Union pursuing ambitious climate goals.

“The green transition is going to going to slow radically in the short term, with the euro-crown one of the reasons,” Wiqvist said.

The weaker currency did help lift Sweden’s exports by 6% in the year to July, despite slower global growth.

But currency volatility makes planning tricky even for exporters, said Jan Soderstrom, CEO of Quintus Technologies, which makes advanced presses used in sectors like aerospace and consumer electronics.

Higher import prices as a result of the crown’s slide could also mean the central bank must keep interest rates higher for longer to fight inflation, piling pain on households and businesses struggling with loan repayment costs.

Another hike to 4.0% on Sept. 21 is widely expectedand banking group Nordea says another could come in November before policy tightening ends.

That could deepen and lengthen a downturn the EU already predicts will make Sweden one of the bloc’s worst-performing economies this year.

“The Riksbank is between a rock and a hard place. On the one hand they want to get inflation down … on the other hand they don’t want to crash the economy,” Nordea Chief Economist Annika Winsth said.

MYSTERY

Swedes feeling the pinch have warmed somewhat to the euro in recent months, though a majority want to stick with the crown.

A Demoskop poll this week showed 42% would vote “No” to joining the euro, while 34% would support it. On Sept. 14, 2003, 55.9% voted to reject membership, and no major party is pushing for a new referendum.

But why the crown has lost around 30% of its value against the single currency over the last 10 years is unclear.

Sweden’s economy is strong, state finances are healthy – government debt is among the lowest in the EU – and its well-capitalized banks are among the region’s most profitable.

In June, accounting firm KPMG said the crown was “mysteriously weak”.

Analysts suggest a number of factors.

Like many central banks, the Swedish Riksbank’s main policy rate was at zero or below from 2014 to 2022 and in 2016 it even threatened to intervene in the foreign exchange market to weaken the crown.

While the rate has risen to 3.75%, in line with the European Central Bank’s, markets may still perceive the Riksbank is dovish, SEB Senior Economist Robert Bergqvist said.

The shocks of the 2008-9 global financial crisis, COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine may also have encouraged investors towards traditional safe-haven currencies.

The Riksbank’s asset purchases in recent years have made crown securities less liquid, reducing their appeal for foreign investors. Uncertainty around Sweden’s accession to NATO – prompted by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and currently blocked by Turkey – could also be a negative factor.

Sweden’s real estate market, burdened by rising interest rates and heavy debts is a worry, although the Riksbank says there is little risk to financial stability.

It also says an economic slowdown will not be too deep, after Sweden’s economy outperformed its European peers during the pandemic.

“If you look at pricing of bank equity or credit default swaps of the banks … it doesn’t seem to price that kind of risk on the Swedish economy, just on the exchange rate,” central bank deputy governor Martin Floden said earlier this month.

Believing the crown is around 20% undervalued, the Riksbank has hedged its own foreign currency exposure in anticipation of future strengthening.

“We and many others are convinced the crown will strengthen at some time, but we would like to see it happen soon rather than over the long term,” Floden said.