New Hampshire documents year’s first US human death from equine encephalitis

2024.08.27 17:02

By Steve Gorman

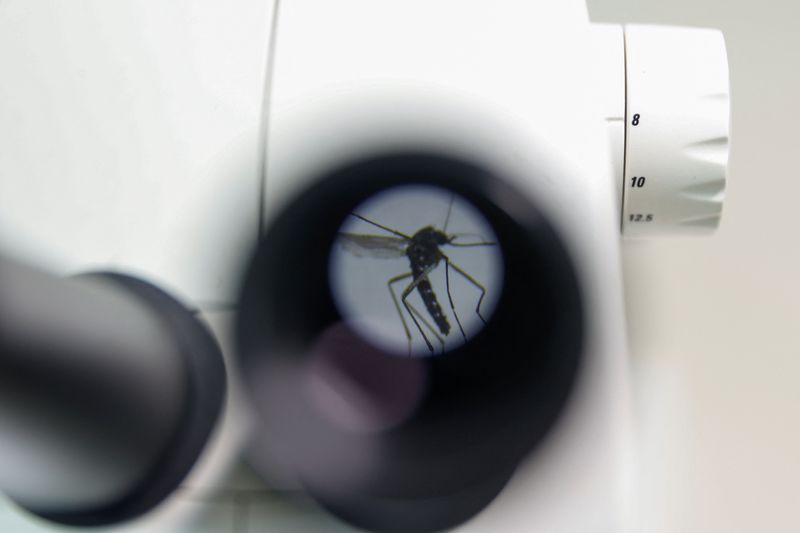

(Reuters) – A New Hampshire resident has died from a rare mosquito-borne brain infection called Eastern equine encephalitis, health officials said on Tuesday, marking the state’s first known human case of the disease in a decade and the fifth this summer in the U.S.

The patient, identified only as an adult from Hampstead, New Hampshire, a town in the state’s southeastern corner, tested positive for the equine virus (EEEV) and was hospitalized with severe central nervous system symptoms before death, according to the state Department of Health and Human Services.

The case was announced after four nonfatal human EEEV infections were reported in the U.S. this year to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: one each in the neighboring New England states of Massachusetts and Vermont and one each in Wisconsin and New Jersey.

The last reported human EEEV case in New Hampshire was in 2014, when three infections were documented, two of them fatal.

In addition to the latest New Hampshire human case, Eastern equine encephalitis has been detected in one horse and seven batches of mosquito samples this summer, state officials said.

In Massachusetts, where a man in his 80s was reported infected in Worcester County – the first human case in that state since 2020 – the virus was found in one horse and 60 mosquito samples, health officials said. It has been detected in 47 mosquito samples in Vermont.

“We believe there is an elevated risk for EEEV infections this year in New England given the positive mosquito samples identified,” New Hampshire’s epidemiologist, Dr. Benjamin Chan, said in a statement. “The risk will continue into the fall until there is a hard frost that kills the mosquitoes.”

Residents should seek to limit exposure when outdoors, he said.

As of last week, Massachusetts state health officials listed at least 10 communities in Plymouth and Worcester counties near Boston as being at high or critical risk for EEEV.

The Eastern equine virus can cause flu-like symptoms such as fever, chills, muscle aches and joint pain, as well as severe neurological disease, including inflammation of the brain (encephalitis) and tissues around the spinal cord (meningitis).

Only about 4% to 5% of people infected with the virus develop encephalitis, but the disease kills roughly a third of those who do. Many others suffer lifelong physical and mental impacts. There is no vaccine or antiviral treatment for the disease.

In the United States, 11 human cases are reported on average each year. Since the CDC began tracking cases nationwide in 2003, the number of human infections documented in a single year peaked in 2019 at 38.

Dr. Amesh Adalja, a senior scholar for the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, said the greatest human risk is in New England and some Gulf Coast states, where incidence of the disease follows cycles of the mosquitoes and the birds they infect.

“The infections are rare, but because of their lethality they attract a lot of attention and public health response,” he said.