Analysis: Tunisia’s Saied savours near total power but faces looming economic tests

2022.07.26 18:33

2/2

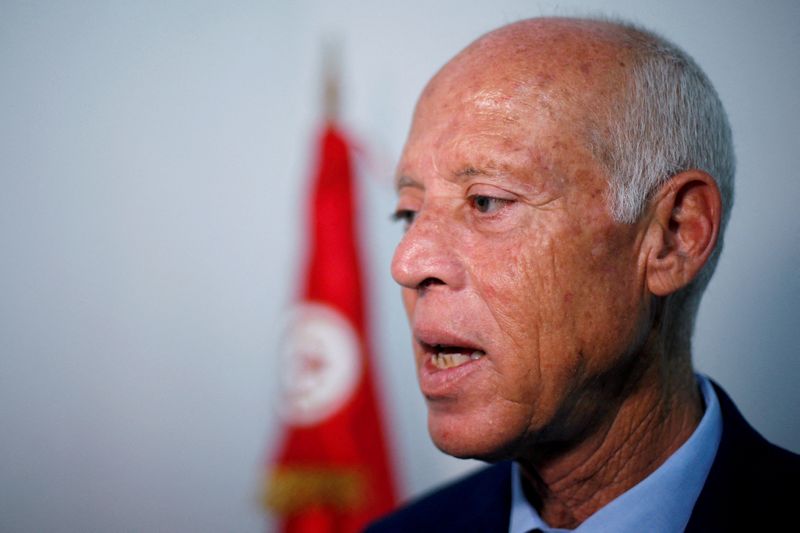

FILE PHOTO: Presidential candidate Kais Saied speaks during an interview with Reuters, as the country awaits the official results of the presidential election, in Tunis, Tunisia September 17, 2019. REUTERS/Muhammad Hamed

2/2

By Tarek Amara and Angus McDowall

TUNIS (Reuters) – By ramming through his new constitution, President Kais Saied has cemented his role as master of Tunisia, heralding a new political era after a brief, difficult experiment with democracy.

An overwhelming ‘yes’ vote in a referendum that brought only about a quarter of voters into polling booths has enshrined a new political system in which the president has nearly total power and few formal checks on his authority.

Glum opponents of his plans fear that Tunisia has now joined the club of failed democracies after leading the uprisings against autocratic rule with a revolution that unleashed the 2011 ‘Arab spring’.

Saied says he will not become a dictator, but as political power flows ever faster into the presidential palace of Carthage, storm clouds loom across the turquoise waters of Tunis bay.

The economic turmoil that over hard years undermined the political parties that shared power through bargains and negotiation is now Saied’s alone to solve in a country with diminishing appetite for failure.

As he moves to consolidate his control over Tunisia through new election laws and a largely toothless legislature, Saied has little choice but to address the unpalatable decisions that have bedevilled his democratic predecessors.

Tunisia’s economy has sickened since 2011, with low growth, rising unemployment, declining public services and growing deficits and debt.

Political instability, militant attacks and then COVID-19 struck repeated hammer blows at an already weak economy, shredding tourism revenue.

Successive governments have had to walk a difficult line, restraining public spending to secure foreign financial help without triggering a social explosion by making life even harder for an impoverished population.

But with no other power bloc left to blame, continued economic problems may be laid at Saied’s door alone.

“After he removed all obstacles and took all powers, he has to meet our urgent demands. We want jobs for our children… We want health and transport services… we cannot wait for long,” said Salem Abidi, a bank clerk in Tunis.

UNILATERAL APPROACH

Passing his referendum may make it easier for Saied to take the first step towards stabilising the economy – securing a long-sought IMF rescue package.

Unlike in the past, there is no need to negotiate within a ruling coalition, and the referendum brings an end to the temporary arrangements in place since last summer. It may also strengthen Saied’s hand with the powerful UGTT labour union that opposes many of the reforms.

“The adoption of the new constitution may increase the chances of reaching an agreement,” said Tunisian economist Moez Joudi.

However, his unilateral political approach could also complicate efforts to unlock further assistance.

Western democracies have been the most important donors to Tunisia since the 2011 revolution. They have said little about his steps and some may be less inclined to support Tunisia than previously.

Others, which would bear the brunt of any migration crisis if Tunisia’s economy collapsed, may think it necessary to back him whatever the ramifications for democracy.

And while Tunisia has said Gulf states have pledged support, none has emerged so far.

However, even if he can secure IMF and other foreign help, Saied has shown little interest in Tunisia’s economy or announced a strategy to restore growth and bring jobs.

“It will not solve the deep economic crisis that needs immediate reforms,” said Joudi of securing an IMF loan.

DISILLUSIONMENT

Economic failures drove disillusionment with democracy and rage at the parties in parliament, unfolding each winter as protests struck Tunisian cities.

“The biggest vulnerability he has is social protest. Given that he has centralised everything in his hands he can no longer blame the others,” said Nadim Houry, executive director of the Arab Reform Initiative.

Such opposition may test Saied’s promise to uphold the rights and freedoms gained after 2011 – and test the loyalty of the security services.

Meanwhile, despite the anger at opposition parties, they still have organised national structures able to mobilise people across the country – and nearly all of them reject the legitimacy of Saied’s moves.

A main opposition coalition has cast doubt on the official turnout figure of 28%. Other senior opposition figures have said even that low rate of participation is insufficient to bless a permanent new political order.

But while they remain divided, and if he can fend off economic collapse, that may not pose a big problem for Saied.

“He’s not the overwhelmingly popular leader that all Tunisians support but he is more popular than anybody else,” said Youssef Cherif, head of the Colombia Global Centers in Tunis.